挥发性卤代烃(VHCs)不仅是温室气体,而且对大气臭氧层的破坏起到很重要的作用[1-3]。VHCs可直接吸收大气红外辐射产生热能导致全球温度升高,还可以通过参与一系列大气化学反应间接影响到全球气候和地表温度。作为平流层中卤素的主要载体,氯甲烷(CH3Cl)在平流层活性氯的含量中占比可达16%,溴甲烷(CH3Br)占活性溴含量的比值高至30% [4]。碘甲烷(CH3I)是含量最丰富的含碘化合物,尤其在低层大气中参与重要的大气化学反应[5]。海洋是大气中CH3Cl、CH3Br和CH3I的主要来源[6-7]。除了人为来源产生的卤代烃之外,在海洋中,浮游植物释放产生CH3Cl[8-10], CH3Br[11]和CH3I[9]是一个重要的天然途径[2, 6, 7, 12-13],但是浮游植物产生卤代烃受环境因素的影响很大[14]。

目前已经有研究表明部分藻类产生的卤代烃会随着温度的增加而增加,但是温度的影响对于不同微藻的产生结果不尽相同[15]。根据Snoeijs和Prentice的研究结果,在波罗的海大部分藻类都会在温度升高之后迅速繁殖。但是Abrahamsson指出没有一个固定的模式适用于所有的藻类,环境的影响因素依旧需要深入探究[15-17]。文献表明微藻在不同盐度下生长有所不同,不同藻类的盐度适应度是不同的[18-20]。关于光照对VHCs释放量的影响,研究结果并不完全统一[21-24]。盐度和光照是海藻生长的重要影响因素,而VHCs的产生和藻类的生长有着不可分割的联系,所以盐度和光照对VHCs的产生也可能产生一定的影响。

球形棕囊藻是海洋中一种数量丰富的球形藻类。它是海洋浮游植物中能够在不同温度和盐度下生存的一类植物。球形棕囊藻是海洋初级生产中的关键物种,它可以大量繁殖增加[25-28],且能产生导致全球变暖和破坏臭氧层的VHCs[13, 29]。球形棕囊藻在不同生长环境(温度、盐度和光照强度)下产生VHCs的含量和生产速率的系统研究暂未见报道,所以本实验主要以中国边缘海的藻类生长环境为基础,探究不同温度、盐度和光照强度下CH3Cl、CH3Br和CH3I产生的浓度和生产速率的释放特性。

1 材料与方法 1.1 藻类培养球形棕囊藻藻种来源于中国海洋大学海洋污染生态化学实验室,藻的培养和取样方法按照文献[29]进行。藻于3L培养瓶中密闭培养,采用f/2培养液并已进行高温灭菌(LDZX-50KBS, 上海申安医疗器械厂)。培养所用的海水采集于黄海,并用0.45 μm醋酸纤维滤膜进行过滤[30]。所有使用的玻璃器皿都在10% HCl浸泡24 h后,用高纯水冲洗干净并经过高温灭菌。不同生长温度(15、20和25 ℃),盐度(19、23和29)和光照(14、25、38 μmol·m-2·s-1)条件于培养期间严格控制。在培养期间,每两天采集1次样品。为了避免浮游植物细胞沉淀,将样品每天摇动3次。

1.2 培养条件藻类培养在培养光照箱中进行(GXZ-380B, 宁波江南仪器厂)。设置温度分别为15、20和25 ℃[31];盐度模拟中国近海盐度范围,确定为19、23和29;考虑到光照强度对藻类生长的促进或抑制效应,设定光照条件为14、25和38 μmol·m-2·s-1,光暗周期12 h:12 h。具体的藻类培养条件设置见表 1。

|

|

表 1 球形棕囊藻的培养条件 Table 1 Different growth environments of Phaeocystis globosa |

隔天取样时间为在开始照射3 h后的上午9:00,每组实验设置3个平行样分别采集以分析细胞密度和卤代烃[31]。根据文献[32-33],通过吹扫捕集气相色谱法(Agilent 6890 N)和电子捕获检测(ECD)分析藻类产生卤代烃的含量。该方法的CH3Cl、CH3Br和CH3Cl的检测限分别为1.8、0.2和0.05 pmol·L-1,精密度分别为<2%、<8%和11%。采用光学显微镜(Olympus CX31,日本Japan)测量藻细胞数。卤甲烷的最大生产速率是由卤代烃对数生长期的变化值除以对数生长期的平均藻细胞数得到的。

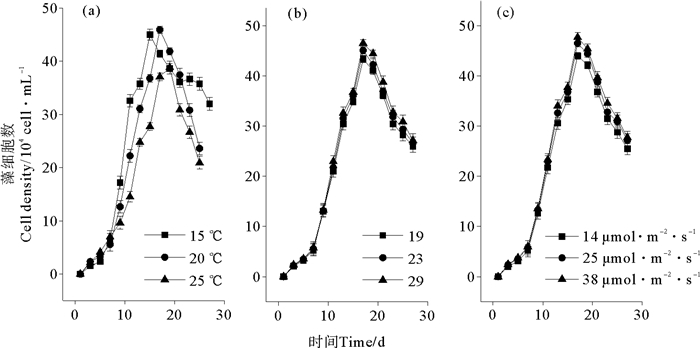

2 结果与分析 2.1 温度、盐度和光照强度对球形棕囊藻细胞密度的影响球形棕囊藻大多数是以1~10 mm左右的形态存活在球形菌落中[31, 35],观察细胞密度可以直接捕捉到菌落的形成情况。在对数生长期开始前的第1周,细胞密度增加缓慢,但在对数生长期期间,菌落会逐渐消失并被单细胞所代替。Scarratt和Moore认为[31, 35]这可能也和培养过程中不断摇晃培养瓶以促进藻细胞新陈代谢有关。温度、盐度和光照在藻类生长中起相当重要的作用(见图 1),在本研究中,生长曲线以及藻类的生长周期在这几种条件下都比较相近。细胞密度在第7天之前基本处于延滞期,之后以对数形式开始增加,在稳定期细胞密度达到了最高点。对于温度的变化对细胞密度影响的结果见图 1(a),从中可以看出,3种温度下球形棕囊藻分别在第15、17和19天达到细胞密度峰值,且15和20 ℃的峰值相近。相比25 ℃,偏低的15~20 ℃更有利于球形棕囊藻的生长(P<0.05)。盐度和光照(P>0.05)的变化对藻细胞密度的影响与温度的变化相比不明显(见图 1(b)和(c))。

|

图 1 温度(a)、盐度(b)和光照(c)对球形棕囊藻细胞密度的影响 Fig. 1 Effect of temperature (a), salinity (b) and light density (c) on cell density of P. globosa |

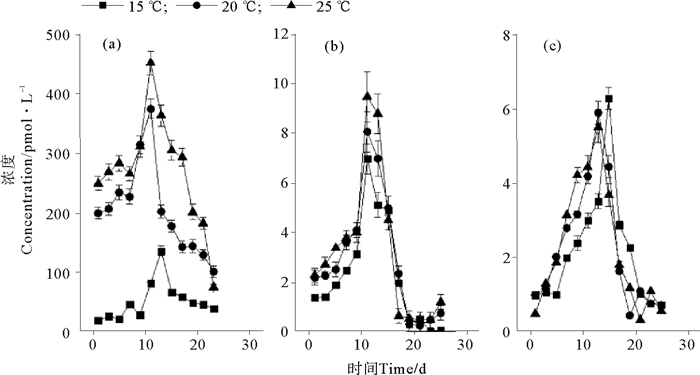

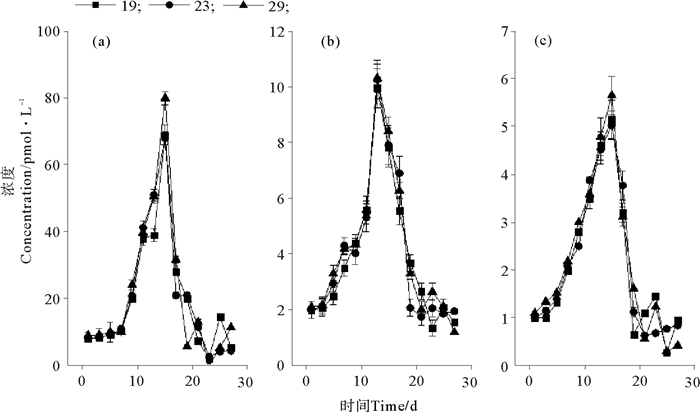

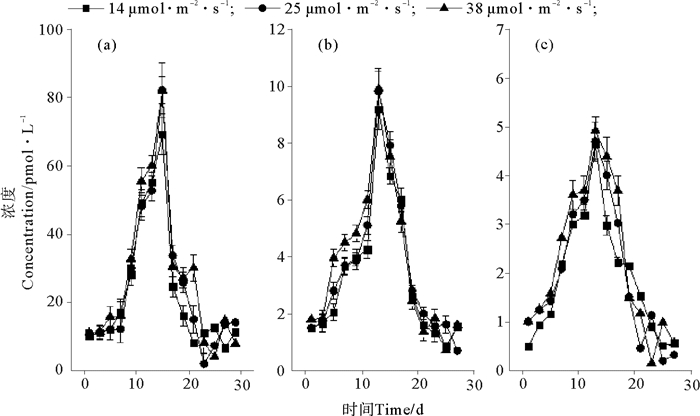

在球形棕囊藻的整个培养周期均能检测出CH3Cl、CH3Br和CH3I,总体上3种物质浓度的变化趋势相似,均表现出对数生长期浓度迅速增加,在稳定生长期及衰亡期降低的趋势。

温度对卤代烃浓度的影响见图 2。25 ℃培养条件下CH3Cl(见图 2(a))和CH3Br(见图 2(b))的浓度最大,分别为452.48和9.49 pmol·L-1。CH3I在这3种温度下的最大浓度差异不大,但在15 ℃时最大浓度略偏高(P<0.05),为6.29 pmol·L-1(见图 2(c))。3种化合物均在第13~15天达到浓度的峰值。盐度和光照对3种化合物浓度的影响如图 3、4所示。可以看出,卤甲烷浓度并没有受到盐度和光照的太大影响。盐度为29时,CH3Cl、CH3Br和CH3I的最大浓度略高于其它条件,分别为79.97、10.31和5.65 pmol·L-1。在38 μmol·m-2·s-1培养条件中,CH3Cl、CH3Br和CH3I的最大浓度分别为82.00,9.90和4.91 pmol·L-1。在整体培养中,发现与CH3Cl相比,CH3Br和CH3I的浓度约低10倍。

|

图 2 不同温度下CH3Cl(a)、CH3Br(b)和CH3I(c)的浓度变化 Fig. 2 The concentrations of CH3Cl (a), CH3Br (b) and CH3I (c) at different temperatures |

|

图 3 不同盐度下CH3Cl(a)、CH3Br(b)和CH3I(c)的浓度变化 Fig. 3 The concentrations of CH3Cl (a), CH3Br (b) and CH3I (c) at different salinities |

|

图 4 不同光照下CH3Cl(a)、CH3Br(b)和CH3I(c)的浓度变化 Fig. 4 The concentrations of CH3Cl (a), CH3Br (b) and CH3I (c) at different light densities |

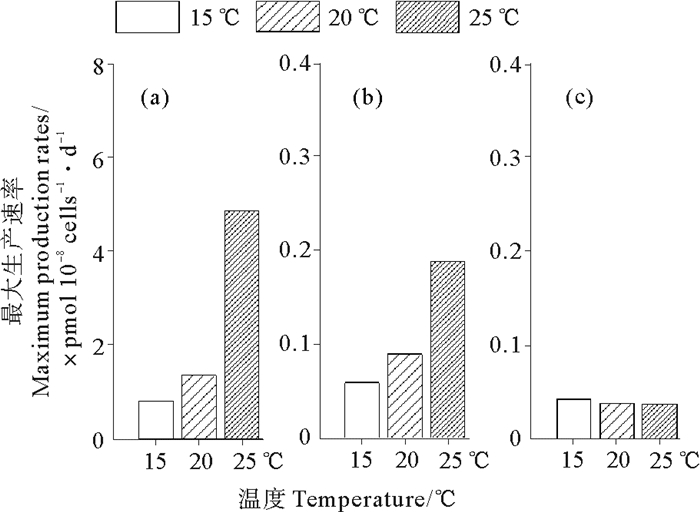

本文按照文献[32]计算了不同温度下卤甲烷的最大生产速率。最大生产速率是以对数生长期变化最大的数据计算,可以更清楚地表明温度变化对藻产生卤甲烷的影响[34]。而盐度和光照对于卤甲烷平均浓度的影响不大(P>0.05),所以本文只计算了温度变化条件下卤甲烷的最大生产速率。3种卤甲烷在不同温度条件下的最大生产速率如图 5所示。温度越高,CH3Cl和CH3Br的最大生产速率越高(见图 5(a), (b)),而CH3I的最大生产速率在3种温度下变化不大。在25 ℃时,CH3Cl和CH3Br的最大生产速率分别达到4.84×10-8和0.19×10-8 pmol·L-1·cells-1·d-1。CH3Cl在3种卤甲烷中最大生产速率最大,明显高于CH3Br 10倍高于CH3I 100倍左右。

|

图 5 不同温度对CH3Cl(a), CH3Br(b), CH3I(c)最大生产速率的影响 Fig. 5 Effect of temperature, salinity, light density on maximum production rate of CH3Cl (a), CH3Br (b), and CH3I (c) |

结果表明藻细胞密度受温度影响最大,而盐度和光照的改变几乎没有产生太大影响。根据之前对盐度效应的研究,某些微藻可以在大范围的盐度范围下生长,但这取决于藻的种类,不同藻类对环境的适应性不同[19-20, 35-37]。图 1(b)中不同盐度下生物量变化不大,说明球形棕囊藻能够适应较大范围的盐度区间。随着盐度的增加,卤甲烷的浓度也有微弱的增加。球形棕囊藻在盐度为29时CH3Cl、CH3Br和CH3I的浓度均最高,但是不同卤甲烷的浓度有差别,这是因为它们的产生机理不同。CH3Cl是占主导地位的有机氯化物,其具有广泛的天然来源,文献曾提出CH3Cl产生过程中存在“甲基氯转移酶”这一机理[38]。另外CH3Cl和CH3Br可能由CH3I和相应的其他卤化物之间的反应形成[39],这也可以解释在所有培养体系中,CH3Cl的浓度总是最高,而CH3Br和CH3I的浓度偏低的现象。

光照对藻细胞密度的影响和盐度的变化具有相似的结果,说明球形棕囊藻也能适应较大范围的光照条件。已有的研究结果表明,光照对藻类释放卤代烃的影响结论差异较大,与藻的种类密切相关[21, 40]。本研究光照的影响结果和盐度的影响相似,卤甲烷的浓度随着光照强度的增加而略有增加。在光照条件下,卤甲烷的形成可能依赖于光合作用的机制,一种和卤过氧化酶相关的合成途径[41-43]。这种卤过氧化酶可以使过氧化氢和卤化物进行反应生成卤甲烷,由于过氧化氢可以在光合作用过程中形成,影响了不同光照下卤甲烷浓度的略微差异。

温度是影响藻类生长的最关键因素之一[44]。本文结果表明温度偏低更适宜球形棕囊藻的生长,不仅最早达到藻细胞密度峰值,而且藻细胞密度也更高。Medlin等人报道在1997年东海海域球形棕囊藻爆发时的海水表层温度为18~24 ℃,且指出球形棕囊藻的适宜生长温度为16 ℃[45]。同时,其他研究也选择15 ℃作为球形棕囊藻的室内培养温度[46],这表明本文的结果与上述文献研究结果相一致。球形棕囊藻不同温度下产生的CH3Cl、CH3Br和CH3I的浓度各有差异,低温适宜球形棕囊藻的生长而25 ℃下产生的CH3Cl和CH3Br最多,且最大生产速率也是随温度升高而增大,这是因为当藻类的适宜生长条件被破坏时,其代谢过程会受到一定的影响,从而释放出更多的卤甲烷[47],这也与文献报道藻类释放卤代烃的原因可能是抵抗外界环境条件的不利变化或者捕食是一致的[32]。对于CH3I受温度影响不同于CH3Cl和CH3Br的结果,是因为CH3I的产生不仅由过氧化酶的活性决定,在水体中,卤甲烷的存在还涉及到彼此间的取代反应(如CH3I转化为CH3Br,后者进一步可转化为CH3Cl)和水解反应[48]。本实验中藻释放的CH3Cl和CH3Br的平均浓度高于CH3I,也可能与取代反应有关,当然还涉及到水体中甲基供体和卤离子含量的影响[45]。球形棕囊藻主要在对数期产生大量的卤甲烷,而对数生长期中的自溶过程有可能发生,因为仅在完整的细胞中卤代烃的自溶过程才会出现[29]。在培养后期的浓度降低,至少说明卤甲烷的释放不是藻细胞破碎后的反应产物。然而,从这些实验仍然不清楚卤甲烷是否是细胞内或者是细胞渗出物的反应产物。

已有的近岸现场调查数据显示卤甲烷的浓度和分布会受到海域、季节及生物、人为或者陆地径流等因素的多重影响,并且不同卤甲烷的浓度变化较大。如中国近海调查结果总体上CH3Cl、CH3Br和CH3I的平均浓度变化范围分别为80~250、2.0~12和1~5 pmol·L-1(实验室内部数据)。结合现场调查数据,本文培养实验结果表明,除了温度系列实验外,球形棕囊藻产生这3种卤甲烷的浓度基本符合上述浓度变化范围,最高浓度甚至高于上述范围,这也说明藻类卤代烃的释放对近岸卤代烃的存在起着相当积极的贡献。假设球形棕囊藻释放卤甲烷的行为在海藻中具有一定的相似性,可以预测当近岸藻华发生之时,藻类产生的卤甲烷是海水中卤甲烷的一个重要来源。

4 结语本文研究了温度、盐度和光照强度对球形棕囊藻生长及其释放卤代烃的影响。温度偏低更适宜球形棕囊藻的生长,高温不利于该藻的生长。CH3Cl和CH3Br的浓度和最大生产速率随温度的增大而增加,但偏低温更有益于碘甲烷在水体中的存在。盐度和光照的改变对于藻的生长和卤代烃的释放的影响不如温度变化明显。球形棕囊藻培养期间3种化合物浓度和最大生产速率相差较大,CH3Cl的浓度在各个条件下都比CH3Br和CH3I高出10倍左右,而最大生产速率CH3Cl高于CH3Br 10倍,高于CH3I 100倍左右。

| [1] |

He Z, Yang G, Lu X. Distributions and sea-to-air fluxes of volatile halocarbons in the East China Sea in early winter[J]. Chemosphere, 2013, 90(2): 747-757. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.09.067

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Tokarczyk R, Moore R M. Production of volatile organohalogens by phytoplankton cultures[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 1994, 21(4): 285-288. DOI:10.1029/94GL00009

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Lovelock J E, Maggs R J, Wade R J. Halogenated hydrocarbons in and over the Atlantic[J]. Nature, 1973, 241(5386): 194-196. DOI:10.1038/241194a0

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Hashimoto S, Toda S, Suzuki K, et al. Production and air-sea flux of halomethanes in the western subarctic Pacific in relation to phytoplankton pigment concentrations during the iron fertilization experiment (SEEDS Ⅱ)[J]. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2009, 56(26): 2928-2935. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.07.003

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Yokouchi Y, Nojiri Y, Toom-Sauntry D, et al. Long-term variation of atmospheric methyl iodide and its link to global environmental change[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2012, 39(23): L2805.

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Moore R M, Wang L. The influence of iron fertilization on the fluxes of methyl halides and isoprene from ocean to atmosphere in the SERIES experiment[J]. Deep Sea Research Part Ⅱ: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2006, 53(20-22): 2398-2409. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr2.2006.05.025

(  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Fuhlbrügge S, Quack B, Tegtmeier S, et al. The contribution of oceanic halocarbons to marine and free troposphere air over the tropical West Pacific[J]. Atmospheric Chemistry & Physics, 2015, 15(13): 17887-17943.

(  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Manley S L, Dastoor M N. Methyl halide (CH3X) production from the giant kelp, Macrocystis, and estimates of global CH3X production by kelp1[J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 1987, 32(3): 709-715. DOI:10.4319/lo.1987.32.3.0709

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Manley S L, Dastoor M N. Methyl iodide (CH3I) production by kelp and associated microbes[J]. Marine Biology, 1988, 98(4): 477-482. DOI:10.1007/BF00391538

(  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Manley S L, Goodwin K, North W J. Laboratory production of bromoform, methylene bromide, and methyl iodide by macroalgae and distribution in nearshore southern California waters[J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 1992, 37(8): 1652-1659.

(  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Manley S L, Goodwin K, North W J. Laboratory production of bromoform, methylene bromide, and methyl iodide by macroalgae and distribution in nearshore southern California waters[J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 1992, 37(8): 1652-1659. DOI:10.4319/lo.1992.37.8.1652

(  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Sturges W T, Cota G F, Buckley P T. Bromoform emission from Arctic ice algae[J]. Nature, 1992, 358(6388): 660-662. DOI:10.1038/358660a0

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

柳秋林, 何真, 杨桂朋. 秋季渤海和北黄海海水中挥发性卤代烃的分布与通量[J]. 海洋环境科学, 2015, 34(4): 481-487. Liu Q L, Zhen H E, Yang G P. Distributions and sea-to-Air fluxes of volatile halocarbons in the Bohai Sea and northern Yellow Sea[J]. Marine Environmental Science, 2015, 34(4): 481-487. (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Dai R, Wang P, Jia P, et al. A review on factors affecting microcystins production by algae in aquatic environments[J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2016, 32(3): 51. DOI:10.1007/s11274-015-2003-2

(  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Abrahamsson K, Choo K, Pedersén M, et al. Effects of temperature on the production of hydrogen peroxide and volatile halocarbons by brackish-water algae[J]. Phytochemistry, 2003, 64(3): 725-734.

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Snoeijs P J M, Prentice I C. Effects of cooling water discharge on the structure and dynamics of epilithic algal communities in the northern Baltic[J]. Hydrobiologia, 1989, 184(1): 99-123.

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Snoeijs P J M. Ecology and taxonomy of Enteromorpha species in the vicinity of the Forsmark nuclear power plant (Bothnian Sea)[J]. Acta Phytogeographica Suecica, 1992, 78: 11-23.

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Brown L M. Photosynthetic and growth responses to salinity in a marine isolate of Nannochloris bacillaris (Chlorophyceae)[J]. Journal of Phycology, 1982, 18(18): 483-488.

(  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Sigaud, Siqueira, Aidar T C, et al. Salinity and temperature effects on the growth and chlorophyll-α content of some planktonic aigae[J]. Boletim Do Instituto Oceanográfico, 1993, 41(1-2): 95-103. DOI:10.1590/S0373-55241993000100008

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Rendall D A, Wilkinson M. Environmental tolerance of the estuarine diatom Melosira nummuloides (Dillw.) Ag[J]. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology & Ecology, 1986, 102(s 2-3): 133-151.

(  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Manley S L, Dastoor M N. Methyl halide (CH3X) production from the giant kelp, Macrocystis, and estimates of global CH3X production by kelp[J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 1987, 32(3): 709-715.

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Klick S. The release of volatile halocarbons to seawater by untreated and heavy metal exposed samples of the brown seaweed Fucus Vesiculosus[J]. Marine Chemistry, 1993, 42(3-4): 211-221. DOI:10.1016/0304-4203(93)90013-E

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Collén J, Ekdahl A, Abrahamsson K, et al. The involvement of hydrogen peroxide in the production of volatile halogenated compounds by Meristiella gelidium[J]. Phytochemistry, 1994, 36(5): 1197-1202. DOI:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)89637-5

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Nightingale P D, Malin G, Liss P S. Production of chloroform and other low molecular-weight halocarbons by some species of macroalgae[J]. Limnology & Oceanography, 1995, 40(4): 680-689.

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Wassmann P, Vernet M, Mitchell B G, et al. Mass sedimentation of Phaeocystis pouchetii in the Barents Sea[J]. Marine Ecology Progress, 1990, 66(1-2): 183-195.

(  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Smith W O, Codispoti L A, Nelson D M, et al. Importance of Phaeocystis blooms in the high-latitude ocean carbon cycle[J]. Nature, 1991, 352(6335): 514-516. DOI:10.1038/352514a0

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Ditullio G R, Grebmeier J M, Arrigo K R, et al. Rapid and early export of Phaeocystis antarctica blooms in the Ross Sea, Antarctica[J]. Nature, 2000, 404(6778): 595-598. DOI:10.1038/35007061

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Vogt M, O'Brien C, Peloquin J, et al. Global marine plankton functional type biomass distributions: Phaeocystis spp.[J]. Earth System Science Data Discussions, 2012, 5(1): 405-443. DOI:10.5194/essdd-5-405-2012

(  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Scarratt M G, Moore R M. Production of methyl bromide and methyl chloride in laboratory cultures of marine phytoplankton Ⅱ[J]. Marine Chemistry, 1998, 59(3-4): 311-320. DOI:10.1016/S0304-4203(97)00092-3

(  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Guillard R R L. Culture of Phytoplankton for Feeding Marine Invertebrates[M]. Boston MA: Springer, 1975: 29-60.

(  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Smythe-Wright D, Peckett C, Boswell S, et al. Controls on the production of organohalogens by phytoplankton: Effect of nitrate concentration and grazing[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research, 2010, 115(G3).

(  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Yang G P, Lu X, Song G S, et al. Purge-and-trap gas chromatography method for analysis of methyl chloride and methyl bromide in seawater[J]. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2010, 38(5): 719-722. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2040(09)60046-3

(  0) 0) |

| [33] |

丁琼瑶.中国东海、黄海碘甲烷的浓度分布与海-气通量及藻类释放研究[D].青岛: 中国海洋大学, 2015. Ding Q Y. The Distributions and Sea-to-Air Fluxes of Methyl Iodide and Production by Marine Phytoplankton[D]. Qingdao: Ocean University of China, 2015. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10423-1015712695.htm (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Scarratt M G, Moore R M. Production of methyl chloride and methyl bromide in laboratory cultures of marine phytoplankton[J]. Marine Chemistry, 1996, 54(3-4): 263-272. DOI:10.1016/0304-4203(96)00036-9

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Fabregas J, Herrero C. Growth and biochemical variability of the marine microalga Chlorella stigmatophora in batch cultures with different salinities and nutrient gradient concentration[J]. British Phycological Journal, 1987, 22(3): 269-276. DOI:10.1080/00071618700650331

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Konopka A, Brock T D. Effect of temperature on blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) in lake mendota[J]. Applied & Environmental Microbiology, 1978, 36(4): 572-576.

(  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Tsuruta A, Ohgai M, Ueno S, et al. The effect of the chlorinity on the growth of planktonic diatom Skeletonema costatum (Greville) Cleve in vitro[J]. Nihon-Suisan-Gakkai-Shi, 1985, 51(11): 1883-1886. DOI:10.2331/suisan.51.1883

(  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Tait V K, Moore R M. Methyl chloride (CH3Cl) production in phytoplankton cultures[J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 1995, 40(1): 189-195. DOI:10.4319/lo.1995.40.1.0189

(  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Zafiriou O C. Reaction of methyl halides with seawater and marine aerosols[J]. Journal of Marine Research, 1975, 33(1): 75-81.

(  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Goodwin K D, North W J, Lidstrom M E. Production of bromoform and dibromomethane by giant kelp: Factors affecting release and comparison to anthropogenic bromine sources[J]. Limnology & Oceanography, 1997, 42(8): 1725-1734.

(  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Neidleman S L, Geigert J. Biohalogenation: Principles, Basic roles, and Applications[M]. E. Horwood: Halsted Press, 1986.

(  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Theiler R, Cook J C, Hager L P, et al. Halohydrocarbon synthesis by bromoperoxidase[J]. Science, 1978, 202(4372): 1094-1096. DOI:10.1126/science.202.4372.1094

(  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Butler A, Walker J V. Marine haloperoxidases[J]. Chemical Reviews, 1993, 93(5): 1937-1944. DOI:10.1021/cr00021a014

(  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Eppley R W. Temperature and phytoplankton growth in the sea[J]. Fishery Bulletin, 1972, 70(4): 1063-1085.

(  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Medlin L K, Lange M, Baumann M E M. Genetic differentiation among three colony-forming species of Phaeocystis: Further evidence for the phylogeny of the Prymnesiophyta[J]. International Journal of Hematology, 1994, 33(3): 199-212.

(  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Moore R M. A photochemical source of methyl chloride in saline waters[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2008, 42(6): 1933-1937.

(  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Raven J A, Geider R J. Temperature and algal growth[J]. New Phytologist, 1988, 110(4): 441-461. DOI:10.1111/nph.1988.110.issue-4

(  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Manley S L, de la Cuesta J L. Methyl iodide production from marine phytoplankton cultures[J]. Limnology and Oceanography, 1997, 42(1): 142-147. DOI:10.4319/lo.1997.42.1.0142

(  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 49

2019, Vol. 49