2. 青岛海洋科学与技术国家实验室, 海洋渔业科学与食物产出过程功能实验室, 山东 青岛 266071

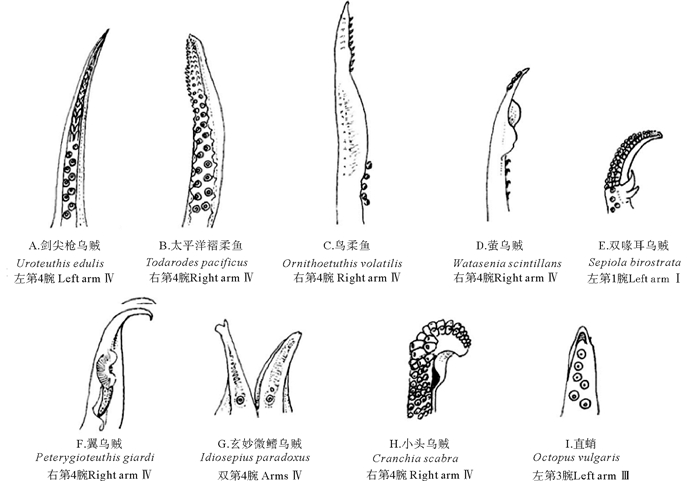

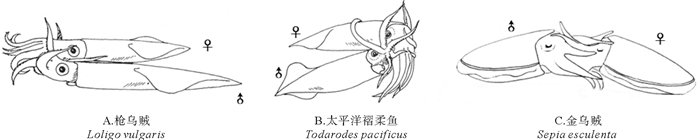

头足类在分类地位上与贝类是近亲,除鹦鹉螺具外壳之外,其他现存头足类均为内壳或壳消失,内壳的形态也因种而异。其神经和感官系统非常发达,同时也具有复杂的交配、产卵行为,属于软体动物门中进化程度最高的一个类群(见图 1)。头足类雌雄交配时,雄体用特化的交接腕(茎化腕)或者终端器把贮藏精子的精荚送到雌体身体的特定部位[1-3]。此时,精荚会发生一系列复杂的变化形成精子囊植入到雌性的外套腔内、输卵管周边或口膜下方等部位[4]。精子从精子囊末端开口逐渐释放出来,部分精子直接与卵细胞结合形成受精卵,部分进入雌性纳精囊以便在后续的产卵过程中利用。随着对头足类交配模式、父权贡献等繁殖行为策略的深入研究,明确精荚的放射、精子囊植入方式和精子进入雌性纳精囊的转运机制、产卵过程中精子的利用方式等,对揭示头足类精子竞争和遗传多样维持机制意义重大。本文主要对头足类雄性生殖系统结构、精荚的放射、精子囊的植入和精子在雌性体内的储存和利用方式等进行综述,以期揭示头足类精子的转运、储存和利用过程及其独特的繁殖、进化机制。

|

图 1 头足类的分类地位 Fig. 1 Taxonomic status of cephalopods |

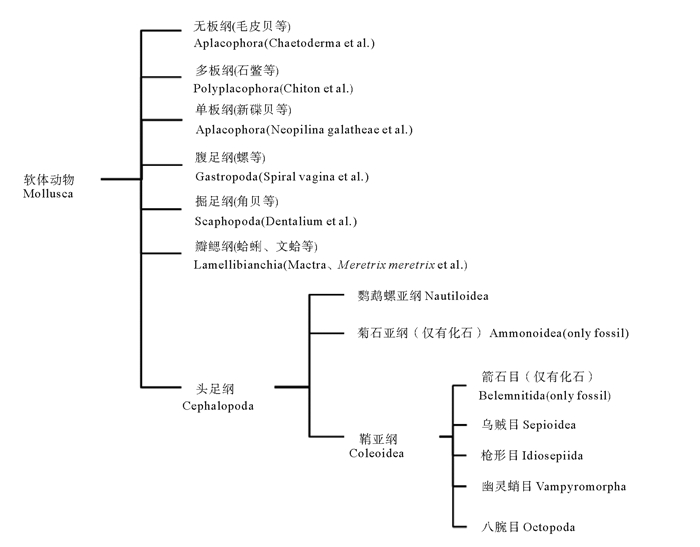

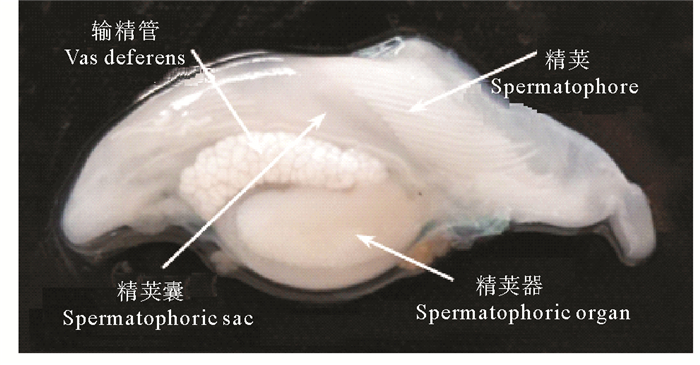

头足类各种属雄性生殖系统的组成基本相同,由精巢(Testis)、输精管(Vas deferens / sperm duct)、精荚器(Spermatophoric organ)或精荚腺(Spermatophoric gland)、精荚囊(Spermatophoric sac)或尼氏囊(Needham’s sac)和阴茎(Penis)组成(见图 2)[5-6]。国外学者还通常将精荚囊和阴茎统称为终端器(Terminal organ),将输精管、精荚器和终端器统称为精荚复合体[7]。

|

(① Reproductive gland; ② Vas deferens; ③ Gonopore; ④ Penis; ⑤ Spermatophoric sac; ⑥ Spermatophoric organ; ⑦ Testis; ⑧ Capsule sac; ⑨ Glandular sac; ⑩ Spermatophoric gland; B11 Prostate; B12 Seminal vesicle; B13 Ampulla. ) 图 2 头足类雄性生殖系统(改编自林东明等[6]) Fig. 2 The male reproductive system of cephalopods(adapted from Lin Dongming[6]) |

精巢是雄性头足类精子形成和成熟的场所,位于外套腔的后端,乳白色,形状各异(球形、心形、椭圆形、圆锥形等)[6]。精巢主要由精巢壁、精小叶和间质组成。精巢壁由大量的结缔组织组成,部分结缔组织向内延伸将精巢分割,形成众多精小叶[8-10]。在精小叶之间还有一定的空隙,称为小叶腔,小叶腔起到聚集成熟精子并将其输送至输精管的作用[10-11]。

1.2 输精管输精管是连接精巢和精荚器的管状结构,主要起将成熟的精子输送至精荚器的作用[6]。八腕目的输精管通常在中部膨大形成储精囊,由此输精管被分成前后两部分[8]。近端输精管通常较细长,高度盘曲,内壁具有大量纤毛,其末端与储精囊相连[12]。储精囊内部具有大量的突起和分泌细胞,这些细胞的分泌物将储精囊中的精子粘合到一起,形成精子团的“雏形”[9]。初步形成的精子团再通过远端输精管进入精荚器中,经过进一步的包装最终形成完整的精荚。乌贼目的输精管细长且高度盘曲,完全展开的输精管可长达20 cm[13],管径较均匀,通常仅在精巢和输精管的连接处形成膨大的壶腹。壶腹具有发达的肌肉层,通过肌肉有节律的伸缩,控制一次进入精荚器的精子刚好能够形成一个精荚[13-14]。

1.3 精荚器精荚器是雄性头足类精荚形成的场所,通常为1个,仅在狼乌贼(Lycoteuthis lorigera)[15]、月乌贼(Selenoteuthis scintillans)、斯普林氏狼乌贼(Lycoteuthis springeri)、霍氏帆乌贼(Histioteuthis hoylei)[5]等少数几个种类中成对出现。枪形目和乌贼目等种类的精荚器由黏液腺、放射导管腺、中被膜腺体、外被膜腺、硬腺和终腺组成[5, 13-14, 16]。黏液腺位于精荚器中部的一侧,与输精管的末端相连,由输精管运送的精子首先进入黏液腺,并与该腺体中的黏液物质混合,形成精子团的雏形[7, 13-14]。放射导管腺前端与黏液腺相连,其管壁向内凹陷在管腔内形成1个大的突起,表面具有大量纤毛,辅助正在形成的精荚向前运动。初步形成的精子团进入放射导管腺被进一步包装,形成内膜、中膜、外膜、胶合体等结构[13-14]。中被膜腺是一个细长直管状的腺体,精荚的中被膜正是在此腺体中形成。此后,正在形成的精荚在外被膜腺包裹上外被膜后便进入硬腺。硬腺是一个长椭圆形的腺体,内壁有大量着生纤毛的纵行褶皱[13-14]。不同种硬腺的功能会有所不同,正在形成的金乌贼(Sepia esculenta)精荚在此腺体中会发生3个显著的变化,即精荚脱水变细、帽子和冠线的形成和头尾的调转[13]。而曼氏无针乌贼(Sepiella maindroni)的精荚并未在此腺体中发生显著变化[14]。终腺是精荚形成的最后一个腺体,从终腺排出的精荚会进入精荚囊。但刚从终腺排出的精荚结构与完全成熟的精荚还有所不同,由此认为精荚在精荚囊中完成最后的形态变化后达到完全成熟[13-14]。而蛸类精荚器是由黏液腺(Mucilagenous gland)或储精囊(Seminal vesicle)、摄护腺或前列腺(Prostate)以及远端输精管(Distal vas deferens)组成[8, 12, 17, 18]。但有学者认为这种划分方式并不能完全体现精荚器的功能,还有待进一步细化[14]。

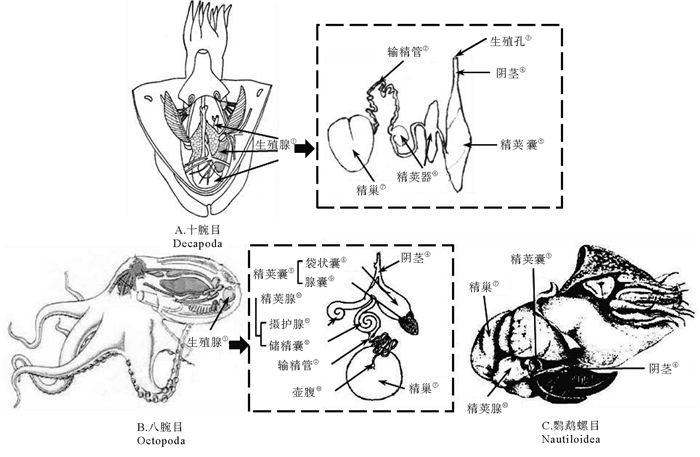

1.4 精荚囊和阴茎精荚囊是雄性头足类暂时储存成熟精荚的场所,囊状,较透明[6]。成熟雄性个体精荚囊中储存的精荚数量和精荚的排列方式存在种间差异。金乌贼精荚囊中的精荚呈螺旋状排列[10],数目多达200~300个(见图 3);狼乌贼单个精荚囊中精荚的数量为55~135个;北太平洋巨型章鱼(Octopus dofleini martini)精荚囊中的精荚尾部朝向阴茎开口,数量较少,仅为10~32个[17];菱鳍乌贼(Thysanoteuthis rhombus)精荚的数量也较少,通常不超过17个[19]。精荚囊壁上发达的肌肉有助于在交配过程中精荚的排出[8, 10],此外,在大王乌贼(Architeuthis dux)中还具有调转精荚方向的作用[7]。精荚囊在前端逐渐变细,形成阴茎,起到排出精荚囊中精荚的作用。在不具有茎化腕的种类中,阴茎还起到将精荚输送给雌性的作用[20]。

|

图 3 金乌贼精荚囊中精荚的排列方式 Fig. 3 The arrangement of spermatophores in the spermatophoric sac of Sepia esculenta |

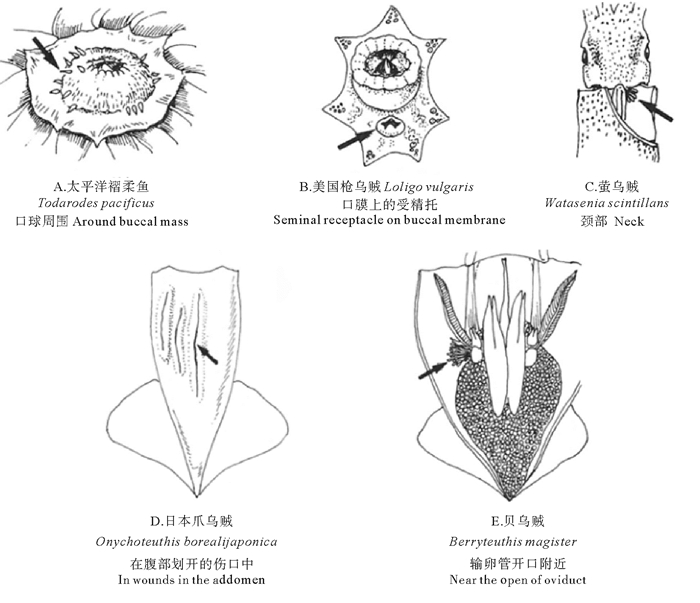

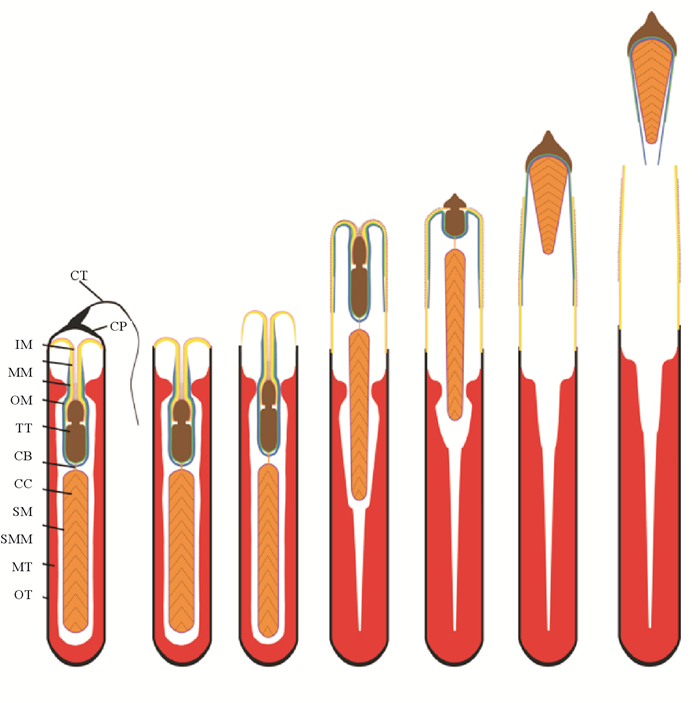

头足类成熟雄性,特定的腕会变形成为交接腕(茎化腕)。雌雄交配时(见图 4),雄性通过茎化腕(见图 5)将精荚转移给雌性[2]。此时,精荚会发生放射反应形成精子囊并植入到雌性个体的口膜腹面或输卵管周边(见图 6)[21-22]。随后,雌性个体会将精子囊中的部分精子储存在纳精囊(一个精子储存器官)中,以供卵子受精使用。头足类的精荚(鹦鹉螺除外)是由外被膜特化而来的帽子结构、弹射装置、胶合体、精子团以及包围它们的复杂的膜鞘结构组成,各部分相互协调、相互配合完成精荚复杂的放射和精子囊神秘的植入过程(见图 7)[23]。位于精荚最前端的帽子结构是精荚发生放射反应的“突破口”。但在不同种类中其形态和开启方式各异。太平洋褶柔鱼(Todarodes pacificus)精荚外被膜在帽子结构处最薄,便于其发生放射反应[22]。而曼氏无针乌贼和普氏枪乌贼(Doryteuthis plei)的外被膜在帽子处最厚,如没有外力作用则不易发生放射反应。但这些种类在帽子顶端形成一条贯穿帽子的凹痕或突起,该凹痕或突起正是精荚发生放射反应的突破口[24-25]。凹痕或突起的一端继续向外延伸形成细长的冠线,冠线则起到传递外力的作用[24-25]。当冠线被拉动时,外力通过冠线传递到帽子结构,导致其在凹痕或凸起处发生断裂,精荚的放射反应由此开启。帽子结构破裂后,弹射装置迅速从精荚中弹出,其中的螺旋丝或黏液管开始外翻。在具有螺旋丝的种类中,位于螺旋丝表面锋利的星形体在精荚植入过程中起到了初步固定的作用,而螺旋丝则在固定处不断“旋入”雌性组织中,从而完成初步的嵌入过程[26]。在不具有螺旋丝的种类中,通常具有一根黏液管[25],其中的黏液和颗粒物质可能起软化溶解组织、辅助胶合体在雌性身体特定部位完成植入的作用[23],但其具体功能还有待进一步研究。此过程的动力主要来自外被膜的渗透作用和中被膜的吸水膨胀。待黏液管或螺旋丝完成外翻后,胶合体开始外翻。通常认为,胶合体的植入是精子囊植入雌性组织最为关键的一步。伴随胶合体的外翻,胶合体会经历一个复杂的结构重塑过程。在此过程中,其前端的尖状结构和其中的黏性物质会进入到雌性组织内,从而完成植入过程[26]。Marian等[27]认为,胶合体植入雌性组织的方式有两种,一种为通过胶合体内的黏液物质粘附在雌性组织上的化学方式,另一种为胶合体前端的尖状结构直接刺入雌性组织的物理方式。Austin等[28]研究发现,皮氏枪乌贼(Loligo pealii)胶合体呈碱性;而普氏枪乌贼的胶合体呈极强的嗜酸性[27]。这些酸碱性不同的成分在精子囊化学植入的过程中起到了十分重要的作用。胶合体植入到雌性组织内部后,精子囊便不再向前移动,空精荚壁(外被膜、中被膜、中膜、内膜)在渗透压的作用下开始向后运动,与中膜相连的外膜和内被膜被不断拉伸直至断裂,空精荚壁脱落,精子囊形成[25]。

|

图 4 头足类的交配方式(改编自奥谷喬司[29]) Fig. 4 The mating patterns of cephalopods(adapted from Takashi OKUTANI[29]) |

|

图 6 精子囊在雌性身体植入的部位(引自奥谷喬司[29]) Fig. 6 The site ofspermatangia implanted in female tissue(cited from Takashi OKUTANI[29]) |

|

(CB:胶合体; CC:连接线; CP:帽子; CT:冠线; IM:内膜; IT:内被膜; MM:中膜; MT:中被膜; OM:外膜; OT:外被膜; SM:精子团; SMM:精子团被膜CB: Cement body; CC: Connecting cylinder; CP: Cap; CT: Cap thread; IM: Inner membrane; IT: Inner tunic; MM: Middle membrane; MT: middle tunic; OM: Outer membrane; OT: Outer tunic; SM: Sperm mass; SMM: Sperm mass membrane.) 图 7 头足类精子囊放射过程的模式图 Fig. 7 Pattern diagram of spermatophoric reaction of cephalopods |

根据精子囊植入雌性组织深浅不同可将精子囊植入分为3种类型(见图 8):(1)浅植入型:仅精子囊的基部植入到雌性的组织中,如金乌贼[30]、滑柔鱼(Illex illecebrosus)[31]、福氏枪乌贼(Loligo forbesi)[32]、火神蛸(Vulcanoctopus hydrothermalis)[33]等;(2)深植入型:精子囊全部或者大部分植入到了雌性的组织中,如大王乌贼[7]、南太平洋爪乌贼(Onychoteuthis meri-diopacifica)[34]、狼乌贼[15]等;(3)塞入型:精子囊被塞入远端输卵管,并通过输卵管进入到输卵管腺或卵巢中,如大爱尔斗蛸(Eledone massyae)[35]、北太平洋巨型章鱼[17]、真蛸(Octopus vulgaris)[36]等。此外,精子囊植入的位置也存在种间差异,如曼氏无针乌贼和金乌贼植入到雌性口膜腹面[25, 37],耳乌贼科的某些种类植入到雌性交配囊内[38],长枪乌贼(Loligo bleekeri)、普氏枪乌贼则植入到雌性外套腔内开放的输卵管附近[39-41]。

|

(A.深植入型(细长型精子囊,如大王乌贼科、小头乌贼科等); B.深植入型(球形精子囊,如蛸乌贼科、耳乌贼科等); C.浅植入型(如枪乌贼科、柔鱼科等); D.塞入型(如大部分八腕目种类)。A. Deep implantation (elongated spermatangium, e.g. Architeuthidae, Cranchiidae); B. Deep implantation (bulbous spermatangium, e.g. Octopoteuthidae, Sepiolidae); C. Shallow implantation (e.g. Loliginidae, Ommastrephidae); D. Plugged attachment (e.g. incirrate octopods).) 图 8 头足类精子囊的植入类型(改编自Marian等[42]) Fig. 8 Types ofspermatangium attachment in female tissue of cephalopods(adapted from Marian[42]) |

精子囊植入的类型可能与头足类不同的生活方式有关。头足类通过外套腔的伸缩吸水和喷水来维持自身运动,植入到雌性身体表面的精子囊则会暴露在巨大的水阻力中,这样不仅会增大雌性个体在运动过程中的能量消耗,还大大增加精子囊丢失的风险[26]。因此,在深水性、运动速度较快的种类中,精子囊通常深深地植入到雌性组织内部[7, 43],从而降低了精子囊丢失的风险。在近岸水域、运动速度相对较慢的种类中,精子囊则植入到雌性口膜腹面[25, 30]。精子囊植入的类型可能还与交配和产卵的时间间隔有关。在交配一段时间后才开始产卵的种类中,精子囊的植入类型通常为深植入型[44],这样可以大大减少产卵前精子不必要的损失;而在繁殖过程中不断交配的种类中,精子囊的植入类型通常为浅植入型[25, 30],这样更有利于其中精子快速的释放。此外,强烈的精子竞争也可能会对精子囊的植入类型产生影响。头足类雌性个体通常会与多个雄性个体交配导致多重父权的产生[45]。而雄性个体则会采取不同的方式将自己的父权最大化[21, 46],如用腕抹除或用漏斗喷出的水柱冲洗之前交配留下的精子囊[30, 47]。与植入较浅的精子囊相比,植入更深的精子囊在交配过程中更不容易被移除。

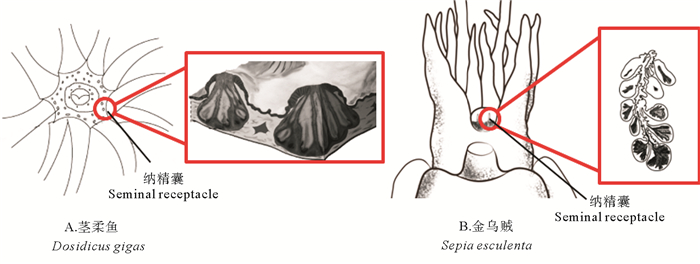

4 精子的储存和利用头足类精子的储存十分重要,能够保证其在交配一次后连续多天产出受精卵。目前,国外学者相继报道了福氏枪乌贼[32]、欧洲横纹乌贼(Sepia officinalis)[48]、澳大利亚巨乌贼(Sepia apama)[49]、玄妙微鳍乌贼(Idiosepius paradoxus)[50]等十足目头足类雌性纳精囊的组织结构,而国内学者仅对曼氏无针乌贼进行过相关报道[25]。在没有纳精囊的种类中,精子全部储存于植入到雌性身体特定部位的精子囊中[7]。而在具有纳精囊的种类中,精子囊中的部分精子还可以长期储存在纳精囊中(见图 9)[25, 48],但关于精子从精子囊到纳精囊的转运机制还尚未有定论。有学者认为,雌性个体的某些行为可能对精子的转运起到了积极的作用。如雌性玄妙微鳍乌贼会通过口膜的扩张收集植入到身体各处的精子囊[51],而雌性加勒比珊瑚乌贼(Sepioteuthis sepioidea)则会用腕拾取精荚,并将其放在纳精囊附近[2]。Oordt[52]研究发现,到达枪乌贼(Loligo vulgaris)纳精囊开口附近的精子已经不再活跃,其精子只能依靠纳精囊肌肉的收缩才能进入纳精囊。还有学者认为,精子是通过自身的运动进入到纳精囊中的[53]。但由于精子囊开口和纳精囊开口并不直接相连,通常认为雌性的精子储存器官能够分泌某些物质吸引精子向其自发运动,从而大幅减少精子在运动过程中的损失。Hirohashi等[54]研究发现,小个体长枪乌贼的精子具有聚集和二氧化碳的趋向性,而这些特性可能在精子向纳精囊转运的过程中起到了十分重要的作用。此外,雌性个体的某些组织结构可能会对精子进入纳精囊起到辅助作用[55],如纳精囊中央管中的纤毛、纳精囊附近的沟槽结构等。进入纳精囊的精子在其底部的排列通常十分有序,头部均朝向纳精囊的内壁,而尾部则主要占据纳精囊的空腔[50, 53],该现象在蛇和鸟类中也普遍存在[55]。头足类的纳精囊除具有储存精子的功能以外,还具有抑制精子活性和营养精子的功能。叶德峰[25]研究发现,曼氏无针乌贼纳精囊中的白色物质能够使原本活跃的精子逐渐变得不活跃,认为纳精囊具有抑制精子活性的作用。Sato等[50]研究发现,玄妙微鳍乌贼纳精囊底部液泡边缘有大量糖类物质出现,由此推测纳精囊具有营养精子的作用。

|

图 9 头足类的纳精囊 Fig. 9 The seminal receptacle of cephalopods |

头足类具有复杂的繁殖行为。在繁殖季节,雄性个体通过精荚器(由黏液腺、放射导管腺、中被膜腺、外被膜腺、硬腺和终腺组成)将精子包装在精荚中。交配时,雄性个体通过茎化腕或终端器将精荚传递给雌性,在此过程中,精荚发生放射反应并最终将精子囊植入到雌性身体的特定部位。精子囊末端开口,其中的精子在产卵过程中逐渐被释放出来,与卵细胞结合形成受精卵。在具有纳精囊的种类中,精子还会进入纳精囊中长期储存,在随后的产卵过程中逐渐被利用。而目前,国内外学者对头足类雄性生殖系统的结构和功能进行了较多研究,但有关精子的转运、储存和利用过程等方面仍存在较多空白。如精荚在放射过程中产生穿透雌性组织机械力的大小、胶合体的化学成分在精子囊植入过程中发挥的作用等还有待进一步研究;有关精子进入纳精囊的过程仅停留在推测和静态观察阶段,缺少动态追踪精子从精子囊到纳精囊转运过程的系统研究;精子在纳精囊中长期储存机制尚不明确;纳精囊具有很多储精小囊,雌性个体能否选择性地动用不同小囊中的精子来控制后代的父系等仍有待进一步探讨。因此,利用动态示踪、生化分析、分子生物学等多种手段,系统研究头足类精子的转运、储存和利用过程将是未来的研究热点。上述研究将有助于更全面、深入地揭示头足类精子竞争和遗传多样性的维持与进化机制,为提高头足类人工繁育效率,有效开展资源增殖与保护提供科学依据。

| [1] |

Arkhipkin A I, Laptikhovsky V V. Observation of penis elongation in Onykia ingens: Implications for spermatophore transfer in deep-water squid[J]. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 2010, 76(3): 299-300. DOI:10.1093/mollus/eyq019

(  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Hanlon R T, Messenger J B. Cephalopod Behaviour[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

(  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Hoving H J T, Vecchione M. Mating behavior of a deep-sea squid revealed by in situ videography and the study of archived specimens[J]. The Biological Bulletin, 2012, 223(3): 263-267. DOI:10.1086/BBLv223n3p263

(  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Drew G A. Sexual activities of the squid Loligo pealii (Les.). Ⅱ. The spermatophore; its structure, ejaculation and formation[J]. Journal of Morphology, 1919, 32(2): 379-435. DOI:10.1002/jmor.1050320205

(  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Arkhipkin A I. Reproductive system structure, development and function in cephalopods with a new general scale for maturity stages[J]. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science, 1992, 12: 63-74. DOI:10.2960/J.v12.a7

(  0) 0) |

| [6] |

林东明, 陈新军. 头足类生殖系统组织结构研究进展[J]. 上海海洋大学学报, 2013, 22(3): 410-418. Lin D M, Chen X J. Research progress on histological structure of reproductive system in cephalopod[J]. Journal of Shanghai Ocean University, 2013, 22(3): 410-418. (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Hoving H J, Roeleveld M, Lipinski M, et al. Reproductive system of the giant squid Architeuthis in South African waters[J]. Journal of Zoology, 2004, 264(2): 153-169. DOI:10.1017/S0952836904005710

(  0) 0) |

| [8] |

许星鸿, 阎斌伦, 郑家声, 等. 长蛸生殖系统的形态学与组织学观察[J]. 动物学杂志, 2008, 43(4): 77-84. Xu X H, Yan B L, Zheng J S, et al. Morphology and histology of the reproductive system in Octopus variabilis[J]. Chinese Journal of Zoology, 2008, 43(4): 77-84. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0250-3263.2008.04.013 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

许著廷, 李来国, 王春琳, 等. 嘉庚蛸生殖系统结构观察[J]. 水产学报, 2011, 35(7): 1058-1064. Xu Z T, Li L G, Wang C L, et al. Anatomy and histology observation on the reproductive system of Octopus tankahkeei[J]. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2011, 35(7): 1058-1064. (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

尹亚南.金乌贼生殖系统结构特征和卵子发生的研究[D].上海: 上海海洋大学, 2018. Yin Y N. Studies on Structure of Reproductive System and Oogenesis in Sepia Esculenta Hoyle[D]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ocean University, 2018. (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

蒋霞敏, 符方尧, 李正, 等. 人工养殖曼氏无针乌贼生殖系统的解剖学与组织学研究[J]. 中国水产科学, 2008, 15(1): 63-72. Jiang X M, Fu F Y, Li Z, et al. Anatomy and histology of reproductive system in cultured Sepiella maindroni[J]. Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 2008, 15(1): 63-72. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1005-8737.2008.01.008 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Stoskopf M K, Oppenheim B S. Anatomic features of Octopus bimaculoides and Octopus digueti[J]. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 1996, 27(1): 1-18.

(  0) 0) |

| [13] |

宋訓民. 金乌贼(Sepia esculenta Hoyle)精荚器的结构和精荚的生成[J]. 山东大学学报(自然科学版), 1963(3): 80-93. Song X M. The structure of spermatophoric organ and the formation of spermatophore in Sepia esculenta Hoyle[J]. Journal of Shandong University, 1963(3): 80-93. (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

叶德锋, 吴常文, 吕振明, 等. 曼氏无针乌贼(Sepiella maindroni)精荚器的结构及精荚形成研究[J]. 海洋与湖沼, 2011, 42(2): 207-212. Ye D F, Wu C W, Lv Z M, et al. Fine structure of spermatophoric organ and formation of spermatophore in Sepiella maindroni[J]. Oceanologia Et LimnologiaSinica, 2011, 42(2): 207-212. (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Hoving H, Lipinski M, Roeleveld M, et al. Growth and mating of southern African Lycoteuthis lorigera (Steenstrup, 1875)(Cephalopoda; Lycoteuthidae)[J]. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 2007, 17(2-3): 259-270. DOI:10.1007/s11160-006-9031-9

(  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Sabirov R, Golikov A, Nigmatullin C M, et al. Structure of the reproductive system and hectocotylus in males of lesser flying squid Todaropsis eblanae (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae)[J]. Journal of Natural History, 2012, 46(29-30): 1761-1778. DOI:10.1080/00222933.2012.700335

(  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Mann T R R, Martin A W, Thiersch J B. Male reproductive tract, spermatophores and spermatophoric reaction in the giant octopus of the North Pacific, Octopus dofleini martini[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 1970, 175(1038): 31-61. DOI:10.1098/rspb.1970.0010

(  0) 0) |

| [18] |

焦海峰, 施慧雄, 尤仲杰. 嘉庚蛸雄性生殖系统组织学观察[J]. 上海海洋大学学报, 2010, 19(3): 333-338. Jiao H F, Shi H X, You Z J. Histological study of reproductive system of the male Octopus tankahkeei[J]. Journal of Shanghai Ocean University, 2010, 19(3): 333-338. (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Nigmatullin C M, Arkhipkin A I, Sabirov R M. Age, growth and reproductive biology of diamond-shaped squid Thysanoteuthis rhombus (Oegopsida: Thysanoteuthidae)[J]. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 1995, 124: 73-87. DOI:10.3354/meps124073

(  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Nesis K N. Mating, spawning, and death in oceanic cephalopods: A review[J]. Ruthenica, 1996, 6(1): 23-64.

(  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Iwata Y, Sakurai Y. Threshold dimorphism in ejaculate characteristics in the squid Loligo bleekeri[J]. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2007, 345: 141-146. DOI:10.3354/meps06971

(  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Takahama H, Kinoshita T, Sato M, et al. Fine structure of the spermatophores and their ejaculated forms, sperm reservoirs, of the Japanese common squid, Todarodes pacificus[J]. Journal of Morphology, 1991, 207(3): 241-251. DOI:10.1002/jmor.1052070303

(  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Hoving H J T, Nauwelaerts S, Van Genne B, et al. Spermatophore implantation in Rossia moelleri Steenstrup, 1856 (Sepiolidae; Cephalopoda)[J]. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2009, 372(1-2): 75-81. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2009.02.008

(  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Marian J E A. Spermatophoric reaction reappraised: novel insights into the functioning of the loliginid spermatophore based on Doryteuthis plei (Mollusca: Cephalopoda)[J]. Journal of Morphology, 2012, 273(3): 248-278. DOI:10.1002/jmor.11020

(  0) 0) |

| [25] |

叶德锋.曼氏无针乌贼精子包装、传递及储存研究[D].舟山: 浙江海洋大学, 2011. Ye D F. Sperm Packaging, Transmitting and Storing in Sepiella maindroni[D]. Zhoushan: Zhejiang Ocean University, 2011. (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Marian J E A. A model to explain spermatophore implantation in cephalopods (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) and a discussion on its evolutionary origins and significance[J]. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2012, 105(4): 711-726. DOI:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01832.x

(  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Marian J E, Domaneschi O. Unraveling the structure of squids' spermatophores: A combined approach based on Doryteuthis plei (Blainville, 1823)(Cephalopoda: Loliginidae)[J]. Acta Zoologica, 2012, 93(3): 281-307. DOI:10.1111/j.1463-6395.2011.00503.x

(  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Austin C R, Lutwakmann C, Mann T. Spermatophores and spermatozoa of the squid Loligo pealii[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 1964, 161(983): 143-152. DOI:10.1098/rspb.1964.0085

(  0) 0) |

| [29] |

奥谷喬司. イカはしゃべるし、空も飛ぶー面白いイカ学入門[M]. 東京: 講談社, 1989.

(  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Wada T, Takegaki T, Mori T, et al. Sperm displacement behavior of the cuttlefish Sepia esculenta (Cephalopoda: Sepiidae)[J]. Journal of Ethology, 2005, 23(2): 85-92. DOI:10.1007/s10164-005-0146-6

(  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Durward R, Vessey E, O'dor R, et al. Reproduction in the squid, Illex illecebrosus: First observations in captivity and implications for the life cycle[J]. Journal of the Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science, 1980(6): 7-13.

(  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Lum-Kong A. A histological study of the accessory reproductive organs of female Loligo forbesi (Cephalopoda: Loliginidae)[J]. Journal of Zoology, 1992, 226(3): 469-490. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb07493.x

(  0) 0) |

| [33] |

González A, Guerra A, Pascual S, et al. Female description of the hydrothermal vent cephalopod Vulcanoctopus hydrothermalis[J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2008, 88(2): 375-379. DOI:10.1017/S0025315408000647

(  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Bolstad K, Hoving H. Spermatangium structure and implantation sites in onychoteuthid squid (Cephalopoda: Oegopsida)[J]. Marine Biodiversity Records, 2011, 4: 5. DOI:10.1017/S175526721000120X

(  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Perez J A A, Haimovici M, Cousin J C B. Sperm storage mechanisms and fertilization in females of two South American eledonids (Cephalopoda: Octopoda)[J]. Malacologia, 1990, 32(1): 147-154.

(  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Wells M, Wells J. Sexual displays and mating of Octopus vulgaris Cuvier and O. cyanea Gray and attempts to alter performance by manipulating the glandular condition of the animals[J]. Animal Behaviour, 1972, 20(2): 293-308. DOI:10.1016/S0003-3472(72)80051-4

(  0) 0) |

| [37] |

张东雪, 张秀梅, 李文涛, 等. 金乌贼精子释放及精子活力的研究[J]. 中国海洋大学学报(自然科学版), 2019, 49(1): 28-33. Zhang D X, Zhang X M, Li W T, et al. Effect determination of spermiation and motility observation of sperm in Sepia esculenta[J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2019, 49(1): 28-33. (  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Akalin M, Salman A. Spermatangia implantation in subfamily Sepiolinae (Cephalopoda Sepiolidae)[J]. Vie Et Milieu - Life and Environment, 2018, 68(2-3): 119-125.

(  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Apostólico L H, Marian J E. Dimorphic male squid show differential gonadal and ejaculate expenditure[J]. Hydrobiologia, 2018, 808(1): 5-22. DOI:10.1007/s10750-017-3145-z

(  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Iwata Y, Sakurai Y, Shaw P. Dimorphic sperm-transfer strategies and alternative mating tactics in loliginid squid[J]. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 2014, 81(1): 147-151.

(  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Iwata Y, Shaw P, Fujiwara E, et al. Why small males have big sperm: dimorphic squid sperm linked to alternative mating behaviours[J]. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 2011, 11(1): 236-244. DOI:10.1186/1471-2148-11-236

(  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Marian J E A R. Evolution of spermatophore transfer mechanisms in cephalopods[J]. Journal of Natural History, 2015, 49(21-24): 1423-1455. DOI:10.1080/00222933.2013.825026

(  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Jackson G D, Jackson C H. Mating and spermatophore placement in the onychoteuthid squid Moroteuthis ingens[J]. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2004, 84(4): 783-784. DOI:10.1017/S0025315404009932

(  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Hoving H J, Bush S L, Robison B H. A shot in the dark: Same-sex sexual behaviour in a deep-sea squid[J]. Biology Letters, 2011, 8(2): 287-290.

(  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Buresch K C, Maxwell M R, Cox M R, et al. Temporal dynamics of mating and paternity in the squid Loligo pealeii[J]. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2009, 387: 197-203. DOI:10.3354/meps08052

(  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Hanlon R T. Mating systems and sexual selection in the squid Loligo: How might commercial fishing on spawning squids affect them?[J]. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations Report, 1998, 39: 92-100.

(  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Hall K, Hanlon R. Principal features of the mating system of a large spawning aggregation of the giant Australian cuttlefish Sepia apama (Mollusca: Cephalopoda)[J]. Marine Biology, 2002, 140(3): 533-545. DOI:10.1007/s00227-001-0718-0

(  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Hanlon R, Ament S, Gabr H. Behavioral aspects of sperm competition in cuttlefish, Sepia officinalis (Sepioidea: Cephalopoda)[J]. Marine Biology, 1999, 134(4): 719-728. DOI:10.1007/s002270050588

(  0) 0) |

| [49] |

Naud M J, Shaw P W, Hanlon R T, et al. Evidence for biased use of sperm sources in wild female giant cuttlefish (Sepia apama)[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2005, 272(1567): 1047-1051. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2004.3031

(  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Sato N, Kasugai T, Ikeda Y, et al. Structure of the seminal receptacle and sperm storage in the Japanese pygmy squid[J]. Journal of Zoology, 2010, 282(3): 151-156. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00733.x

(  0) 0) |

| [51] |

Kasugai T. Reproductive behavior of the pygmy cuttlefish Idiosepius paradoxus in an aquarium[J]. Venus (Japanese Journal of Malacology), 2000, 59(1): 37-44.

(  0) 0) |

| [52] |

Oordt G V. The spermatheca of Loligo vulgaris. I. Structure of the spermatheca and function of its unicellular glands[J]. Journal of Cell Science, 1938, 80(s2): 593-599.

(  0) 0) |

| [53] |

Fernández- lvarez F, Villanueva R, Hoving H J T, et al. The journey of squid sperm[J]. Reviews in Fish Biology & Fisheries, 2018, 28(1): 191-199.

(  0) 0) |

| [54] |

Hirohashi N, Iwata Y. The different types of sperm morphology and behavior within a single species: Why do sperm of squid sneaker males form a cluster?[J]. Communicative & Integrative Biology, 2013, 6(6): e26729-3.

(  0) 0) |

| [55] |

Neubaum D M, Wolfner M F. 3 Wise, winsome, or weird? Mechanisms of sperm storage in female animals[J]. Current Topics in Developmental Biology, 1998, 41: 67-97. DOI:10.1016/S0070-2153(08)60270-7

(  0) 0) |

2. Functional Laboratory of Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Process, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266071, China

2019, Vol. 49

2019, Vol. 49