2. 中国海洋大学海洋环境与生态教育部重点实验室,山东 青岛 266100

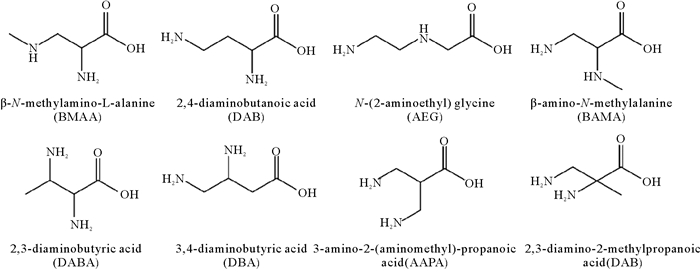

β-N-甲氨基-L-丙氨酸(β-N-methylamino-L-alanine, BMAA)是一种具有神经毒性的非蛋白质氨基酸(见图 1)。BMAA的电离常数为pK1=2.10,pK2=6.48,pK3=9.70,等电点pI=8.09[1],化学性质稳定,易溶于水,属于双性离子,在生理条件下(pH=7.4)呈中性[2]。目前自然界中存在7种已知的BMAA同分异构体,分别是2, 4-二氨基丁酸(2, 4-diaminobutyric acid, DAB)、N-2-氨乙基甘氨酸[N-2-(aminoethyl) glycine, AEG]、β-氨基-N-甲基丙氨酸(β-amino-N-methylalanine, BAMA)、2, 3-二氨基丁酸(2, 3-diaminobutyric acid, DABA)、3, 4-二氨基丁酸(3, 4-diaminobutyric acid,DBA)、3-氨基-2-(氨甲基-)丙酸[3-amino-2-(aminomethyl)-propanoic acid, AAPA]和2, 3-二氨基-2-甲基丙酸(2, 3-diamino-2-methylpropanoic acid, DMA)[3]。其中,DAB和AEG是BMAA最为常见的两种同分异构体,均具有神经毒性[4]。

在生物体内,BMAA既能以游离态的形式存在,又能与多肽和蛋白质类物质结合,以蛋白结合态的形式存在[5]。但生物体内两种形态BMAA的比例不是固定不变的,在一定条件下可以互相转化[6]。

2 BMAA的来源、生物合成及其影响因素 2.1 来源人们最早在苏铁的种子中发现了BMAA,随后发现苏铁珊瑚状根部的念珠藻(Nostoc sp.)可能是苏铁种子中BMAA的初始来源[1]。后来研究发现,水生环境中生长的念珠藻属的蓝细菌普遍检出BMAA,包括淡水、咸淡水、河口、海洋及陆地生态环境[1-7]。另外,研究人员还在微囊藻属(Microcystis)、颤藻属(Oscillatoria)、浮丝藻属(Planktothrix)和束丝藻属(Aphanizomenon)等不同蓝细菌样品中检出BMAA[7]。目前已报道的蓝细菌样品BMAA的检出情况如表 1所示,说明环境中广泛分布的蓝细菌普遍含有BMAA。据报道,几乎所有被测试的实验室菌株[8]、野外分离株[9]、野外样品[10]和共生物种[8]都检出高浓度的BMAA。然而,由于使用非特异性的氨基酸分析方法使得这一结论受到质疑。除一项外[11],几乎所有的研究都不能重现这些最初的结果;在蓝细菌中没有检出BMAA[12];只有一部分样品检出BMAA[13];在所有样品中检出BMAA,但浓度非常低[14]。另外,蓝细菌的BMAA产毒情况还受到外界环境的影响,Downing等人运用同位素标记法,证明了微囊藻Microcystis sp.能够在氮饥饿的情况下合成游离态的BMAA[15]。蓝细菌不稳定的产毒情况使得人们对蓝细菌作为BMAA生物来源的结论更加怀疑,目前仍存在争议。

|

|

表 1 世界各地蓝细菌样品中BMAA的检出情况 Table 1 Detection of BMAA in cyanobacterial samples around the world |

自2003年首次报道蓝细菌产生BMAA以来,很多研究聚焦蓝细菌的BMAA生物合成机制,将其视为环境BMAA的主要来源。2014年,Jiang等人首次在分离自瑞典西海岸的5种硅藻中检出BMAA,说明海洋硅藻可能是BMAA的生物来源[21]。随后研究人员将注意力转向硅藻合成BMAA的调查研究,在野外和实验室培养的海洋硅藻中检出BMAA,包括Achnanthes sp.、Navicula pelliculosa、Skeletonema marinoi、Proboscia inermis、Phaeodactylum tricornutum、Chaetoceros calcitrans、Thalassiosira pseudonana[22]。从澳大利亚淡水水域分离的5株淡水硅藻也有4株检出BMAA[23],说明淡水硅藻也可能产生BMAA。由于硅藻是海洋生态系统中重要的浮游植物类群,这一发现说明海洋食物链可能是人类暴露接触BMAA的重要途径。甲藻在演化历程中晚于蓝细菌但早于硅藻,甲藻是否产生BMAA引起了人们的关注。Lage等人在葡萄牙常常发生甲藻藻华的水域采集的贝类样品中检出BMAA,发现贝类BAAA含量与链状裸甲藻(Gymnodinium catenatum)的密度有关,据此推测甲藻也可能产生BMAA。此外,在实验室培养的链状裸甲藻细胞中也检出了BMAA((0.457±0.186) μg/g DW)[24]。随后报道了海洋甲藻三角异冒藻(Heterocapsa triquetra)能够产生BMAA[25-26]。然而,自从Liang等人报道海洋甲藻产生BMAA以来[18],暂未见有关其他种类的甲藻含有BMAA的报道,有待进一步确认。

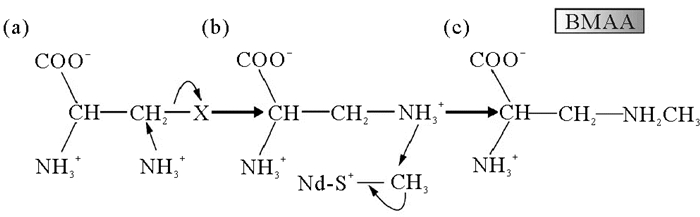

2.2 BMAA的生物合成机制的初步研究当前人们对生物合成BMAA的机制尚不清楚,仅对苏铁合成BMAA的途径提出了假设。BMAA的化学结构属于丙氨酸在β位发生取代反应的产物[26],其生物合成的底物可能是磷酸丝氨酸、半胱氨酸、邻乙酰丝氨酸或氰基丙氨酸。参考Brenner等人的报道,一个可能的BMAA生物合成途径如图 2所示,合成游离BMAA的步骤只需要两步反应,第一步是通过半胱氨酸合酶蛋白催化的亲核反应,将NH3转移到丙氨酸的β位碳原子;第二步反应是在合成物上添加CH3以产生BMAA[27]。在苏铁的EST(表达序列标签)文库中确定了这两个酶促反应的候选基因,其中有两个EST能够编码半胱氨酸合酶,而第二步需要的甲基转移酶也能在苏铁EST文库中找到。除此之外,S-腺苷甲硫氨酸(SAdM)是最有可能成为甲基供体的氨基酸。总之,苏铁含有参与BMAA生物合成相关酶的候选基因。由于许多肽中含有N-甲基,另一种猜想是通过游离的2, 3-二氨基丙酸(2, 3-DAP)在大分子结构内直接发生甲基化而合成BMAA,随后通过小分子或大分子的代谢周转以游离态形式释放,而一部分BMAA仍作为大分子的一部分保持结合,即现在所定义的沉淀结合态BMAA[27-28],这个过程常用的甲基来源可能是S-腺苷甲硫氨酸。

|

图 2 通过两步反应合成苏铁BMAA的机制假说 Fig. 2 Hypothesis for the biosynthesis of BMAA through two-step pathway in cycads |

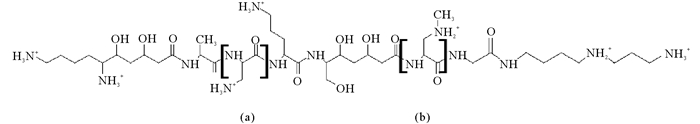

有关蛋白结合态BMAA的生物合成,也有研究猜测甲胺取代蛋白质中磷酸丝氨酸残基的O-磷酸基团及磷酸苏氨酸残基中的N-甲基基团,从而形成与蛋白结合的BMAA[29]。由丝氨酸或半胱氨酸残基衍生且包含在蛋白质或肽中的脱氢丙氨酸残基在加入甲胺后,在高pH条件下能够产生BMAA。但是这种合成反应不太可能在体内自发进行,因为高pH值条件的甲胺来源难以实现[30]。许多原核生物通过非核糖体肽合成机制(NRPS)生物合成多种活性肽,如环肽节球藻毒素和微囊藻毒素[31-32],蓝细菌也可能通过这种方式将BMAA结合到肽中。在筛选芽孢杆菌属新抗生素的过程中,从新几内亚土壤样品中分离到的粉状芽孢杆菌(Bacillus pulvifaciens)的菌株,能产生三种或三种以上的抗生素,经吸附、洗脱、分离后得到三个活性成分I、II、III。其中,组分I和II因其氨基酸组成而分别被命名为galantin I和galantin II。galantin I是目前已知的唯一含有BMAA结构的肽类化合物(见图 3),经酸水解后可以释放S-2, 3-DAP和S-BMAA[33-34]。因此,也可能是游离形式的2, 3-DAP通过NRPS掺入到肽类化合物中,然后经转甲基酶对其甲基化,从而形成蛋白结合态的BMAA。

|

(方括号内的氨基酸残基(a)和(b)分别来自S-2, 3-二氨基丙酸和S-3-N-甲基-2, 3-二氨基丙酸(BMAA)。The amino acid residues (a) and (b) within squared brackets are derived from S-2, 3-diaminopropanoic acid and S-3-N-methyl-2, 3-diaminopropanoic acid (BMAA), respectively. ) 图 3 galantin I的化学结构 Fig. 3 Chemical structure of galantin I |

据报道,微藻或蓝细菌合成毒素的过程是其应对极端环境压力的反应产物[35-37]。例如,环境温度、光照强度和氮营养盐均会影响微囊藻毒素的产生[35-37]。BMAA作为一种藻毒素,其产生机制可能与生态位及环境有关[38]。目前有关环境因子胁迫影响蓝细菌及硅藻产生BMAA的研究较少。Downing等人利用稳定同位素15N研究了蓝细菌中BMAA的生物合成,发现氮饥饿处理会导致细胞内游离态15N-BMAA含量增加,而沉淀结合态BMAA没有变化,饥饿后向培养基中添加NO3-和NH4+会导致游离态BMAA减少,而蛋白结合态BMAA没有相应增加[15]。另据报道,蓝细菌合成游离态BMAA的含量与培养基中氮营养盐浓度呈极显著负相关,与磷营养盐浓度呈弱的正相关,且外源BMAA能抑制某些不产生BMAA的蓝细菌的生长,由此推断BMAA的合成可能是蓝细菌对低氮胁迫的应激反应[39]。硅藻作为BMAA的主要来源之一,其合成BMAA的水平也受到环境压力的影响,特别是氮饥饿和细胞密度相关的压力[40]。从以上结果猜想,在缺氮条件下微藻合成更多的BMAA可能是为了存储更多的氮,作为自身利用氮的储备。这些研究为探究BMAA的生态学意义提供了理论依据。

3 BMAA的食物链传递人与BMAA的暴露接触主要是通过食物链传递,在食用水产品过程中积累毒素。已有大量调查研究发现,世界各地咸水、海水或淡水中的滤食性贝类、甲壳类动物和部分鱼类生物体内含有BMAA[41-46]。在水生生态系统中,初级生产者蓝细菌、硅藻等合成的BMAA可沿着食物网向高营养级生物传递,并在生物体内富集,表现出显著的生物放大作用。例如,在关岛生态系统中游离态BMAA沿着蓝细菌(0.3 μg·g-1)—苏铁种子(9 μg·g-1)—飞蝠(3 556 μg·g-1)构成的食物链传递,生物放大系数达10 000倍以上,且在人的脑组织(7.2 μg·g-1)中也检出了BMAA。同时,蛋白结合态BMAA在不同营养级之间也表现出传递和富集的现象,即蓝细菌(72 μg·g-1)—苏铁种子(89 μg·g-1)—飞蝠(146 μg·g-1)—人脑组织(627 μg·g-1)[47]。这表明BMAA在关岛生态系统中存在显著的生物放大作用,且符合食物链中化合物浓度不断增加的经典“金字塔”模型。

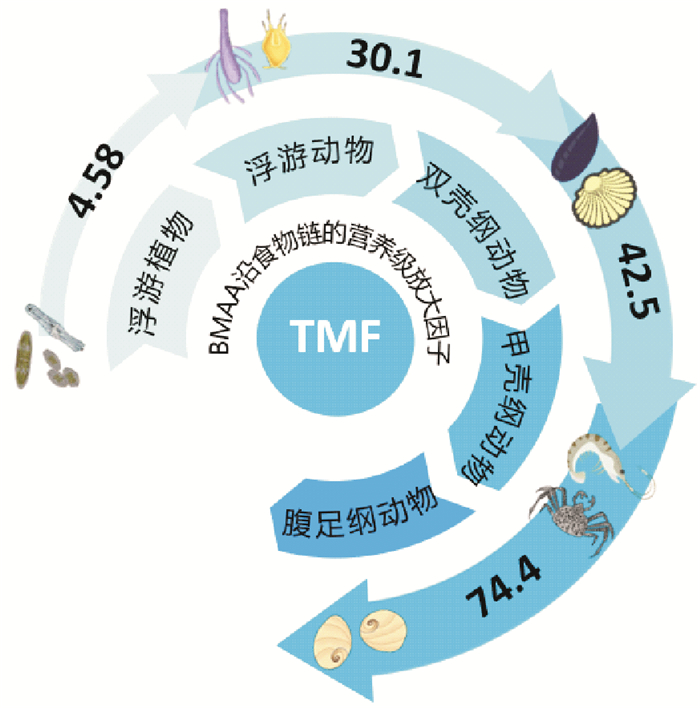

在其他的水生生态系统中也发现了BMAA的生物放大作用。通过长期监测波罗的海蓝细菌和其他海洋生物中BMAA含量发现:直接或间接以蓝细菌为食的高营养级生物体内含有高浓度的BMAA[42]。2013年7月至2014年10月在法国地中海地区收集的浮游生物、附生生物和贻贝体内都检出了BMAA(0.58、2.6、4.0 μg·g-1干重),并确定硅藻可能是这些生物体内BMAA的主要来源[43]。在中国胶州湾生态系统中BMAA在浮游动物、双壳类软体动物、甲壳类节肢动物和腹足类软体动物体内的营养放大系数(TMF)分别是4.58、30.1、42.5和74.4[48] (见图 4)。

|

图 4 中国胶州湾海域BMAA的传递途径及各级的营养放大系数 Fig. 4 Transfer of BMAA along food chains and its trophic magnification factors (TMF) in Jiaozhou Bay, China |

同样,在淡水水生生态系统中也存在BMAA的生物放大作用。在Finjasjön湖中根据鱼类种类、总重量、性别和收集季节确定BMAA在底栖鱼类和食肉鱼类中的生物积累模式,发现随着鱼类年龄的增加导致鱼类组织内BMAA含量的增加[49]。在我国太湖的贡湖湾,研究人员采集和分析了不同营养级的蓝细菌、软体动物、甲壳类动物和各种鱼类中的BMAA的含量,其平均含量分别为4.12、3.21、3.76和6.05 μg·g-1,表明BMAA可以向高营养级生物传递[50]。在武汉东湖蓝细菌水华暴发期间,微囊藻细胞和鱼体内BMAA含量分别为0.04和0.32 μg·g-1,表明BMAA可在鱼类体内积累并具有一定的生物放大作用[51]。但我国淡水和海洋生态系统中BMAA沿食物链传递行为相比而言,海洋环境中BMAA的生物放大作用更为突出。

4 BMAA的检测方法目前国际上通常采用高效液相色谱-荧光检测法(High performance liquid chromatography-florescence detection, HPLC-FLD)、高效液相色谱-串联质谱联用法(High performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometer/mass spectrometer, LC-MS/MS)、气相色谱-质谱联用法(Gas chromatography-mass spectrometer,GC-MS)和毛细管电泳法(Capillary electrophoresis,CE)等方法分析样品中BMAA的含量,主要以HPLC-FLD和LC-MS/MS两种方法为主。不同的化学分析方法定量环境样品中BMAA的浓度有较大争议,Esterhuizen报道了采用GC-MS测定的BMAA平均浓度比另一项研究中LC-MS测定的平均浓度高近百倍[52-53]。

4.1 高效液相色谱-荧光检测法基于光学检测或质谱分析的方法已广泛应用于环境样品中BMAA的分析。HPLC-FLD分析环境样品中BMAA时,需要先对BMAA进行衍生化处理,生成具有荧光发光基团的衍生物。目前国际上普遍采用6-氨基喹啉基-N-羟基琥珀酰亚氨基甲酸酯(6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl carbamate, AQC)作为BMAA的衍生试剂,能够与游离态BMAA分子上的氨基和甲氨基快速反应生成稳定的喹啉化合物[54]。关岛地区的苏铁、蓝细菌和果蝠等生物样品中的BMAA大都是采用该类方法测得的,并且研究人员利用这种方法在蓝藻样品中普遍检出BMAA[8, 10, 55]。该衍生方法普遍适用于与氨基酸结构类似的大多数化合物,AQC分子可以与氨基酸及其他氨基酸衍生物生成具有荧光发光基团的衍生物,干扰对BMAA衍生物的甄别与定量分析,通常导致过高估算样品中BMAA的浓度,甚至是假阳性结果。同时,HPLC-FLD方法仅依据保留时间和荧光信号进行识别,对目标化合物的选择性较差。

4.2 高效液相色谱-串联质谱联用法高效液相色谱-串联质谱联用法使用串联质谱作为检测器,以保留时间、母离子的质荷比、碰撞诱导解离后产物离子的质荷比以及产物离子丰度的比值作为定性和定量的依据,能够有效提高检测的准确度和灵敏度。该方法被广泛应用于各类生物样品BMAA毒素的分析,主要包括衍生分析法和直接分析法。在衍生法中,常使用AQC为衍生试剂,衍生后的产物经反相色谱柱分离后进入质谱,以变迁离子模式m/z 459 -> 258和m/z 459 -> 171分别作为BMAA定性和定量分析的依据。直接分析法使用亲水交互作用色谱柱(HILIC)分离BMAA及其衍生物,但BMAA和BAMA在HILIC色谱柱上通常难以实现基线分离,不过变迁离子m/z 119 -> 88是BMAA的特征裂解模式,可用于BMAA的定量分析。

比较HPLC-FLD、LC-MS/MS直接分析与衍生化分析三种常用方法检测8个蓝细菌样品和2个对照样品的结果发现,HPLC-FLD方法在苏铁种子和3个蓝藻样品中检出BMAA,两种LC-MS/MS方法仅在阳性对照组(苏铁种子)中检出BMAA[56],说明HPLC-FLD方法可能高估了蓝细菌样品中BMAA的含量。目前部分研究人员对BMAA沿食物链的生物放大效应持质疑态度[57]。这种对生物样品中BMAA含量分析结果的质疑主要源于检测分析BMAA毒素的方法。在分析关岛地区生物样品的研究工作中采用了分析氨基酸的经典方法(HPLC-FLD方法),与LC-MS/MS方法相比该方法对BMAA的特异性较低,且所有含有氨基官能团的氨基酸类化合物衍生物均产生荧光物质。因此,HPLC-FLD对BMAA的定性和定量分析容易受生物样品中氨基酸的干扰,常常会导致色谱峰识别错误或定量结果偏高[58]。这些研究人员认为BMAA属于非亲脂性的氨基酸,不能通过食物链在生物体内传递和积累。据报道,在波罗的海北部海域的调查中发现只有浮游植物、浮游动物和糠虾检测结果呈阳性,而底栖无脊椎动物和鱼类体内均未检出BMAA,故对BMAA在波罗的海食物网中传递的现象提出质疑[45]。尤其是使用LC-MS/MS分析蓝细菌中BMAA的结果通常为阴性,使得人们质疑荧光衍生法在分析蓝细菌样品BMAA时容易产生假阳性结果[59-61]。因此,建议在分析生物样品BMAA毒素时选择灵敏度高、特异性强的LC-MS/MS方法进行分析。

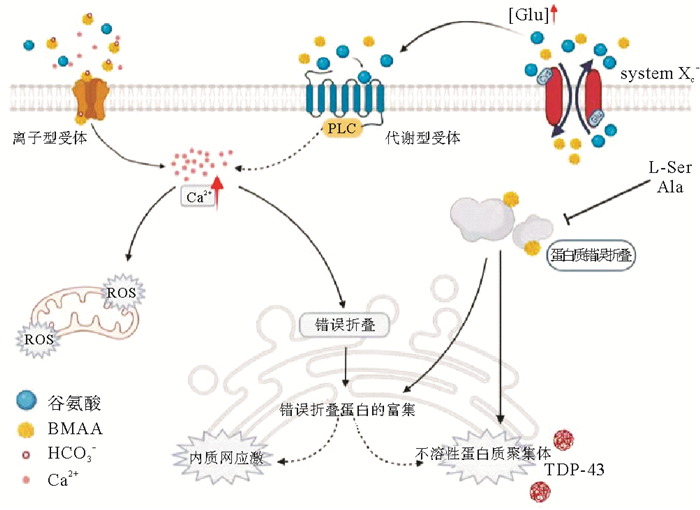

5 BMAA神经毒性的作用机制 5.1 BMAA作为谷氨酸受体激动剂引发兴奋性毒性兴奋性氨基酸(EAA)是神经系统的兴奋性神经递质,包括谷氨酸和天冬氨酸,通过与神经细胞上的EAA受体结合实现动作电位的传导,而过量的兴奋性氨基酸将导致神经元细胞过度刺激而受损,这一过程被称为兴奋性毒性效应[62]。兴奋性毒性被认为是诱发神经退行性疾病的主要原因,临床证据表现为ALS患者脑脊液中的谷氨酸水平升高[63-67]。BMAA可与谷氨酸受体结合,并引起兴奋性毒性,故也被认为是一种神经兴奋性毒素[68]。

谷氨酸受体,尤其是NMDA受体(N-甲基-D-天冬氨酸受体,是离子型谷氨酸受体的亚型)的过度激活与阿尔茨海默症、帕金森痴呆综合症和肌萎缩侧索硬化症的神经元死亡有关[69]。由于NMDA受体激活在兴奋性毒性神经元细胞死亡中起主导作用,这一作用通常被认为是BMAA毒性的主要机制。Weiss和Choi发现,当血浆中的碳酸氢盐离子(HCO3-)浓度超过10 mmol·L-1时,BMAA能够与碳酸氢盐结合生成α-氨基甲酸酯和β-氨基甲酸酯[70],其中β-氨基甲酸盐具有与谷氨酸相似的结构,能够竞争性地与神经细胞膜上的NMDA受体、AMPA受体、促离子型谷氨酸受体(iGluR)和促代谢型谷氨酸受体(mGluR)等多种谷氨酸受体结合[63, 71-74]。当这些谷氨酸受体被激活后,神经细胞内Na+和Ca2+浓度升高,K+浓度降低,从而破坏了细胞稳态,产生离子毒性。同时,细胞内Ca2+浓度的增加破坏了正常的线粒体功能,导致线粒体在有氧呼吸过程中产生的活性氧释放到细胞质中,造成氧化损伤及内质网应激。谷氨酸受体的激活还会导致神经细胞去极化,使得神经细胞膜的通透性增加,并释放去甲肾上腺素,造成兴奋性中毒。

动物实验显示,幼鼠在单次高剂量腹腔注射BMAA毒素1 h后内就出现运动功能性障碍,24 h后大鼠开始出现运动失调,48 h后神经生理损伤表现更为突出[75]。BMAA处理不仅使大鼠出现行为障碍,还引起小脑皮层中多种细胞的退行性改变,如小脑星状细胞、篮状细胞、浦肯野细胞和高尔基细胞等特异性小脑神经元的变形,但谷氨酸能兴奋性颗粒细胞或小脑顶核未见退行性改变,其余的大脑、脊髓和脊神经节也没有出现退行性改变。BMAA的急性兴奋毒性机制在静脉注射1~10 μmol BMAA后的瑞士Webster小鼠后也有所表现,而且这种运动神经元毒性效应可以通过特定抑制剂进行控制[76]。Lindstrom等人证实了BMAA对中枢神经元的亚急性作用[77],在成年雄性Sprague-Dawley大鼠脑内注射BMAA一周后,400 μg大剂量的BMAA损坏了大部分黑质部位,向背部扩散至中脑导水管,而10 μg BMAA对黑质的损伤较小,损伤区域包含酪氨酸羟化酶免疫反应神经元和树突,以及P物质免疫反应终末[77]。在Sprague-Dawley大鼠慢性暴露BMAA后,无论是否使用特异性非NMDA和NMDA受体拮抗剂,都有进一步的兴奋性氨基酸受体亚型(如NMDA、EAA和AMPA)参与[78-79],这些结果进一步证实了BMAA的兴奋性毒性假设。

5.2 BMAA作用于胱氨酸/谷氨酸反向转运蛋白(XC-系统)胱氨酸/谷氨酸反向转运体XC-系统是一种反转运蛋白,介导胱氨酸摄取及谷氨酸的排出。BMAA能够抑制胱氨酸的摄取,导致可用于合成谷胱甘肽的胱氨酸的量减少,细胞谷胱甘肽的耗竭,从而增加细胞的氧化应激,引起自由基介导的神经元死亡[80]。另外,BMAA可能会驱动逆向转运蛋白释放谷氨酸。如,激活的星形胶质细胞可以通过XC-系统释放谷氨酸,从而杀死皮层神经元[81];小胶质细胞也可以通过XC-系统释放谷氨酸,导致小脑颗粒细胞的死亡[82]。通过XC-系统转运,BMAA可以在细胞中积累,并可能结合到蛋白质中[83],蛋白质的错误折叠可能在神经退行性疾病中发挥重要作用。

5.3 BMAA的错误嵌入和细胞应激BMAA一旦进入细胞质,可能被错误地识别为丝氨酸或丙氨酸嵌入到新合成的细胞蛋白中,或者通过非共价键与蛋白质结合[84-85]。BMAA的错误嵌入可能会影响蛋白质的三级结构,导致神经元蛋白质的生物活性受损;或者可能导致蛋白质在翻译过程中的终止或蛋白质从核糖体释放后裂解[86-89]。这种异常蛋白质的合成可能会导致内质网(ER)的细胞应激、氧化还原系统的失调以及一些促凋亡的半胱天冬酶(如caspase-2)的激活,从而导致细胞死亡[90]。蛋白质错误折叠常常导致不溶性聚集体的形成,在受影响组织中聚集体的异常聚集是神经退行性疾病中观察到的主要病理变化之一。在ALS患者诊断过程中,常将TAR DNA结合蛋白(TDP-43)作为一种生物标志物。另外,暴露于BMAA的大鼠海马区内游离态泛素浓度出现明显的降低,该区域还存在高度多泛素化的蛋白质,这表明BMAA诱导了由于错误折叠或聚集而存在缺陷和功能障碍的蛋白质多泛素化。有缺陷的蛋白质被多个泛素分子标记后,会在蛋白酶体中被水解[91]。另一项研究还表明天然泛素与BMAA结合后,泛素的结构会发生改变,从而会导致蛋白质的折叠缺陷[92]。因此,目前认为BMAA是通过多种机制作用于神经元产生兴奋毒性,并诱导神经退行性疾病的发生(见图 5)。

|

图 5 BMAA神经毒性的多种作用机制示意图 Fig. 5 Diagrammatic sketch for the multiple mechanisms of BMAA neurotoxicity |

神经黑色素是在中脑多巴胺神经元内合成,可以防止多巴胺氧化产物的积累,如环化醌,被认为是一种对抗有毒内源性化合物积累的神经元保护机制。神经黑色素缺陷是当前帕金森痴呆症的致病假说之一[93]。目前已知的可诱发帕金森痴呆综合症的有毒化合物,如1-甲基-4-苯基-1, 2, 3, 6-四氢吡啶(MPTP),已被证明能与神经黑色素结合并形成神经毒性复合物[94]。BMAA也能与黑色素结合,可能导致黑色素聚合物的改变,使其在捕获重金属方面的效果降低或对MPTP的降解更敏感[94-95]。BMAA对黑色素正常代谢途径的干扰,会导致儿茶酚胺的代谢物过量,诱导线粒体功能障碍、自由基积累、脂质过氧化、蛋白质降解途径改变和α-突触核蛋白聚集成具有神经毒性的低聚物,导致初级神经元老化[96-100]。通过与神经黑色素的相互作用,即使BMAA没有嵌入蛋白质中,BMAA也可以长期储存,并在整个生命周期中释放,从而可能导致大脑受损,特别是慢性炎症和胶质增生,更容易诱发神经退行性疾病。随着BMAA在大脑中释放,积累到一定浓度时可能对富含神经黑色素的神经元和邻近组织产生神经毒性。

6 BMAA诱导神经退行性疾病假说目前关于BMAA在神经退行性疾病发展过程中的作用仍存在分歧。在ALS及PDC发病率较高的关岛和另外两个西太平洋地区调查发现,BMAA能够沿着食物链(苏铁种子—飞狐—人体)传递并在生物体内放大,最终在人体内富集;而随着食物链中飞狐的灭绝,关岛地区神经退行性疾病发生率也大幅下降[80, 101];并且在关岛肌萎缩侧索硬化症的患者脑组织中检出了BMAA,研究人员认为当地人患肌萎缩侧索硬化症与其食用苏铁种子之间存在联系,苏铁种子中的BMAA可能是神经退行性疾病的主要致病因子[102]。

BMAA还能够通过母乳在哺乳动物间传递。在喂食14C标记的L-BMAA后,母体大鼠能够通过乳汁将L-BMAA转移到后代体内[103],并采用LC-MS/MS和放射自显影技术验证了母婴乳汁传递这一结论。整个过程中幼鼠胃液、肝脏及大脑中的BMAA含量随着母乳喂养时间延长逐渐增加[104]。这项研究引起了诸多学者对这种转移是否会出现在人类母婴之间传递的猜测。目前已经在分化的小鼠乳腺上皮细胞HC11中证实了对[14C] L-BMAA的选择性摄取,而且人乳腺细胞MCF7细胞对[14C] L-BMAA与[14C] D-BMAA的摄取模式与小鼠HC11细胞的摄取结果吻合[105]。这项结果进一步证实BMAA可能通过哺乳传递给婴儿的猜想。在卵生动物中也发现了BMAA的传代富集现象。通过给产卵鹌鹑服用14C标记的BMAA,通过放射自显影及成像分析检查鸟类和鸟卵中的放射性分布,结果显示鸟卵中明显掺入了放射性物质,主要存在于蛋黄中,蛋白中也有检出[106]。这些特殊的传递方式表明人类与野生动物接触BMAA的来源可能比预期的更加多样化。

在散发的神经退行性疾病患者中也证实了BMAA的存在。死于ALS/PDC和无症状的查莫罗人及两名死于阿尔茨海默症(AD)的加拿大人脑组织中均检出BMAA,说明BMAA可能在不同地区的多种神经退行性疾病的发病过程中发挥作用[102]。2006年,Banack等人分析了来自关岛及其附近雅浦岛和萨摩亚岛的飞狐大脑及肌肉样本,发现所有关岛样本中含有高浓度的BMAA,雅浦岛的大多数样本也检出BMAA[107]。Pablo等人在北美的50位死于ALS及AD患者的脑组织样本中有49个检出了BMAA,而在对照组样本中未检出BMAA[107]。这些结果均间接说明BMAA可能是神经退行性疾病的致病因子。

BMAA导致神经退行性疾病ALS/PDC的作用在动物模型中也已被证实。Bell等人对R-X-S鸡与雌性Wistar幼鼠进行腹腔注射D, L-BMAA(0.34~0.82 mg/g体重),发现L-BMAA能够造成鸡和幼鼠后腿协调性受损,而D-BMAA对动物没有影响;较高剂量的BMAA可缩短毒性出现的时间并延长中毒时间,数小时后症状消失,该结果表明L-BMAA对R-X-S鸡与幼鼠具有急性神经毒性作用[108]。以小鼠作为受试生物时也发现了同样的现象[109],小鼠脑腔内注射BMAA后出现“全身颤抖”和“摇晃”等行为障碍,且神经行为损伤与暴露BMAA剂量之间存在相关性[109]。Karlsson等在新生Wistar大鼠脑生长突发期(BGS)期间注射BMAA,导致大鼠出现急性行为缺陷(运动能力受损和多动症)和学习记忆功能的损害,而无任何形态学异常[110]。神经原纤维缠结(NFT)和β-淀粉样蛋白沉积物是AD和ALS-PDC疾病的神经学标志物。Cox等人发现黑长尾猴通过饮食慢性摄入210 mg·kg-1·d-1 BMAA 140 d后能够触发NFT和β-淀粉样蛋白的形成,其结构和密度与死于ALS/PDC的查莫罗人脑组织中发现的症状相似[111]。以上结果表明,BMAA可以诱导神经元损伤,导致类似于ASL/PDC患者的神经退行性病变。

由于ALS/PDC是一种慢性病,暴露于假定的神经毒素后长达30年才能显现出来,而在动物研究中只观察到BMAA的急性毒性效应,并且早期动物模型实验只在摄入大量的BMAA才能产生急性毒性,而通过饮食接触BMAA的浓度可能要低得多。因此部分研究者认为目前关于人体BMAA暴露剂量的证据尚不能支持神经退行性疾病与BMAA之间的联系。BMAA作为ALS/PDC的潜在致病因子被人们重视是从Spencer等人的研究开始,该研究发现灵长类动物食蟹猴口服摄入BMAA后,会出现前角细胞和皮质脊髓束退化,且伴随运动障碍和帕金森痴呆综合症的临床症状[112]。但这项研究被指出使用了高剂量的BMAA,并且在食蟹猴身上观察到的作用是急性且可逆的,没有出现延迟和进行性的现象,这与人类ALS/PDC的神经元变性症状相反,因此该研究受到很多质疑。另外,还有研究发现大鼠皮下注射L-BMAA后,大鼠的神经行为、运动功能及脊髓的神经化学方面存在处理方式和性别依赖性变化[113],BMAA暴露的大鼠神经化学差异与ALS患者组织的变化不一致,这与出生后神经发育的微妙变化有关,而与BMAA的直接兴奋性毒性无关[113]。通过灌胃[114]或喂食颗粒[115]的给药方式,没有观察到小鼠与BMAA暴露后的神经行为、生理或神经病理异常。皮下注射SD大鼠较低剂量的BMAA后,大鼠未见明显的神经元功能障碍。

7 展望随着BMAA在全球水生生态系统中被广泛检出,且越来越多的毒理学实验结果表明BMAA的神经毒性,有关环境中BMAA的健康风险也越来越引起人们的关注。本文综述了BMAA的主要生物来源、生物放大作用、毒性作用机制、可能的生物合成过程及其致病假说的争议。目前有关BMAA的认识仍有欠缺,尚不能确定BMAA的生物合成过程及生态学意义,有关BMAA与ALS-PDC等神经退行性疾病发病机制之间的联系尚未定论,有关蛋白结合态BMAA的结构或功能尚未研究。建议今后从以下几个方面开展研究:

(1) 探究BMAA的生物合成机制。BMAA的生物合成是个非常复杂的过程,虽然已经提出了一些生物合成的假说,但其合成通路尚未得到验证。游离态和蛋白结合态BMAA的生物合成途径是否一致也不清楚。有关BMAA生物合成机制的探索,将有助于对其生物学意义的理解。

(2) 评估BMAA的生态学意义。由于合成BMAA需要消耗能量,在长期进化过程中仍被保留说明BMAA对生产者在保证生态位或提高其生理效率方面可能具有重要功能,但对于其生态学意义尚不清楚。该方面的研究将有助于理解BMAA对水生生物的健康风险。

(3) 解析蛋白结合态BMAA的化学结构与功能。目前在硅藻及其他生物样品中证实了蛋白结合态BMAA的存在形式,但对其化学结构和生物学功能尚不清楚,有待于进一步研究。

| [1] |

Vega A, Bell A E. α-Amino-β-methylaminopropionic acid, a new amino acid from seeds of Cycas circinalis[J]. Phytochemistry, 1967, 6(5): 759-762. DOI:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)86018-5 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

李爱峰, 于仁成, 李锋民, 等. 神经毒素β-N-甲氨基-L-丙氨酸的毒理学与检测方法研究进展[J]. 中国药理学与毒理学杂志, 2009, 23(2): 152-156. Li A, Yu R, Li F, et al. Progresses in toxicology and detection methods for neurotoxin β-N-methylamino-L-alanine[J]. Chinese Journal of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 2009, 23(2): 152-156. DOI:10.3867/j.issn.1000-3002.2009.02.012 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Jiang L, Aigret B, De Borggraeve W M, et al. Selective LC-MS/MS method for the identification of BMAA from its isomers in biological samples[J]. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 2012, 403(6): 1719-1730. DOI:10.1007/s00216-012-5966-y (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Lance E, Arnich N, Maignien T, et al. Occurrence of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) and isomers in aquatic environments and aquatic food sources for humans[J]. Toxins, 2018, 10(2): 83. DOI:10.3390/toxins10020083 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Rosén J, Westerberg E, Schmiedt S, et al. BMAA detected as neither free nor protein bound amino acid in blue mussels[J]. Toxicon, 2016, 109: 45-50. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.11.008 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Murch S J, Cox P A, Banack S A. A mechanism for slow release of biomagnified cyanobacterial neurotoxins and neurodegenerative disease in Guam[J]. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences of The Unitied States of America, 2004, 101(33): 12228-12231. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0404926101 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Cervantes Cianca R C, Baptista M S, Lopes V R, et al. The non-protein amino acid β-N-methylamino-L-alanine in Portuguese cyanobacterial isolates[J]. Amino Acids, 2012, 42(6): 2473-2479. DOI:10.1007/s00726-011-1057-1 (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Cox P A, Banack S A, Murch S J, et al. Diverse taxa of cyanobacteria produce β-N-methylamino-L-alanine, a neurotoxic amino acid[J]. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences of The Unitied States of America, 2005, 102(14): 5074-5078. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0501526102 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Esterhuizen M, Downing T G. β-N-methylamino-l-alanine(BMAA) in novel South African cyanobacterial isolates[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2008, 71(2): 309-313. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2008.04.010 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Metcalf J S, Banack S A, Lindsay J, et al. Co-occurrence of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine, a neurotoxic amino acid with other cyanobacterial toxins in British waterbodies, 1990—2004[J]. Environmetal Microbiology, 2008, 10(3): 702-708. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01492.x (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Baptista M S, Cianca R C C, Lopes V R, et al. Determination of the non-protein amino acid β-N-methylamino-l-alanine in estuarine cyanobacteria by capillary electrophoresis[J]. Toxicon, 2011, 58(5): 410-414. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.08.007 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Rosén J, Hellenäs K. Determination of the neurotoxin BMAA (β-N-methylamino-L-alanine) in cycad seed and cyanobacteria by LC-MS/MS (liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry)[J]. The Analyst, 2008, 133(12): 1785. DOI:10.1039/b809231a (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Faassen E J, Gillissen F, Zweers H A J, et al. Determination of the neurotoxins BMAA (β-N-methylamino-L-alanine) and DAB (α-, γ-diaminobutyric acid) by LC-MSMS in Dutch urban waters with cyanobacterial blooms[J]. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, 2009, 10(sup2): 79-84. DOI:10.3109/17482960903272967 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Jonasson S, Eriksson J, Berntzon L, et al. Transfer of a cyanobacterial neurotoxin within a temperate aquatic ecosystem suggests pathways for human exposure[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of The Unitied States of America, 2010, 107(20): 9252-9257. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0914417107 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Downing S, Banack S A, Metcalf J S, et al. Nitrogen starvation of cyanobacteria results in the production of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine[J]. Toxicon, 2011, 58(2): 187-194. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.05.017 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Cox P A, Banack S A, Murch S J, et al. Diverse taxa of cyanobacteria produce beta-N-methylamino-L-alanine, a neurotoxic amino acid[J]. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences of The Unitied States of America, 2005, 102(14): 5074-5078. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0501526102 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Błaszczyk A, Siedlecka-Kroplewska K, Woźniak M, et al. Presence of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine in cyanobacteria and aquatic organisms from waters of Northern Poland; BMAA toxicity studies[J]. Toxicon, 2021, 194: 90-97. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2021.02.007 (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Esterhuizen M, Downing T G. β-N-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) in novel South African cyanobacterial isolates[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2008, 71(2): 309-313. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2008.04.010 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Violi J P, Mitrovic S M, Colville A, et al. Prevalence of β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) and its isomers in freshwater cyanobacteria isolated from eastern Australia[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2019, 172: 72-81. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.01.046 (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Metcalf J S, Banack S A, Richer R, et al. Neurotoxic amino acids and their isomers in desert environments[J]. Journal of Arid Environments, 2015, 112: 140-144. DOI:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2014.08.002 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Jiang L, Eriksson J, Lage S, et al. Diatoms: a novel source for the neurotoxin BMAA in aquatic environments[J]. Public Library of Science One, 2014, 9(1): e84578. (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Réveillon D, Séchet V, Hess P, et al. Production of BMAA and DAB by diatoms (Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Chaetoceros sp., Chaetoceros calcitrans and, Thalassiosira pseudonana) and bacteria isolated from a diatom culture[J]. Harmful Algae, 2016, 58: 45-50. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2016.07.008 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Violi J P, Facey J A, Mitrovic S M, et al. Production of β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) and its isomers by freshwater diatoms[J]. Toxins, 2019, 11(9): 512. DOI:10.3390/toxins11090512 (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Lage S, Costa P R, Moita T, et al. BMAA in shellfish from two Portuguese transitional water bodies suggests the marine dinoflagellate Gymnodinium catenatum as a potential BMAA source[J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2014, 152: 131-138. DOI:10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.03.029 (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Jiang L, Ilag L. Detection of endogenous BMAA in dinoflagellate (Heterocapsa triquetra) hints at evolutionary conservation and environmental concern[J]. Pub Raw Science, 2014, 2: 1-8. (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Warrilow A G S, Hawkesford M J. Cysteine synthase (O-acetylserine (thiol) lyase) substrate specificities classify the mitochondrial isoform as a cyanoalanine synthase[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2000, 51(347): 985-993. DOI:10.1093/jexbot/51.347.985 (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Brenner E D, Stevenson D W, McCombie R W, et al. Expressed sequence tag analysis in Cycas, the most primitive living seed plant[J]. Genome Biology, 2003, 4(12): R78. DOI:10.1186/gb-2003-4-12-r78 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Arti T, Susan G. Phosphate on, rubbish out[J]. Nature, 2016, 539: 38-39. DOI:10.1038/539038a (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Meyer H E, Hoffmann-Posorske E, Korte H, et al. Sequence analysis of phosphoserine-containing peptides[J]. FEBS Letters, 1986, 204(1): 61-66. DOI:10.1016/0014-5793(86)81388-6 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Nunn P B, Codd G A. Metabolic solutions to the biosynthesis of some diaminomonocarboxylic acids in nature: Formation in cyanobacteria of the neurotoxins 3-N-methyl-2, 3-diaminopropanoic acid (BMAA) and 2, 4-diaminobutanoic acid (2, 4-DAB)[J]. Phytochemistry, 2017, 144: 253-270. DOI:10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.09.015 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Aráoz R, Molgó J, Tandeau De Marsac N. Neurotoxic cyanobacterial toxins[J]. Toxicon, 2010, 56(5): 813-828. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.07.036 (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Pearson L A, Dittmann E, Mazmouz R, et al. The genetics, biosynthesis and regulation of toxic specialized metabolites of cyanobacteria[J]. Harmful Algae, 2016, 54: 98-111. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2015.11.002 (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Shoji J, Sakazaki R, Wakisaka Y, et al. Isolation of galantin Ⅰ and Ⅱ, water-soluble basic peptides[J]. The Journal of Antibiotics, 1975, 28(2): 122-125. DOI:10.7164/antibiotics.28.122 (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Sakai N, Ohfune Y. Total synthesis of galantin Ⅰ revision of the original structure[J]. Tetrahedron Letters, 1990, 31(22): 3183-3186. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)94727-0 (  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Watanabe M F, Oishi S. Effects of environmental factors on toxicity of a cyanobacterium (Microcystis aeruginosa) under culture conditions[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1985, 49(5): 1342-1344. DOI:10.1128/aem.49.5.1342-1344.1985 (  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Van der Westhuizen A J, Eloff J N. Effect of temperature and light on the toxicity and growth of the blue-green alga Microcystis aeruginosa (UV-006)[J]. Planta, 1985, 163: 55-59. DOI:10.1007/BF00395897 (  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Lee S J, Jang M H, Kim H S, et al. Variation of microcystin content of Microcystis aeruginosa relative to medium N: P ratio and growth stage[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2000, 89(2): 323-329. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01112.x (  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Jonasson S, Eriksson J, Berntzon L, et al. Transfer of a cyanobacterial neurotoxin within a temperate aquatic ecosystem suggests pathways for human exposure[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of The Unitied States of America, 2010, 107(20): 9252-9257. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0914417107 (  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Yan B, Liu Z, Huang R, et al. Impact factors on the production of β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) by cyanobacteria[J]. Chemosphere, 2020, 243: 125355. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125355 (  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Lage S, Strom L, Godhe A, et al. Kinetics of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) and 2, 4-diaminobutyric acid (DAB) production by diatoms: The effect of nitrogen[J]. European Journal of Phycology, 2019, 54(1): 115-125. DOI:10.1080/09670262.2018.1508755 (  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Brand L E, Pablo J, Compton A, et al. Cyanobacterial blooms and the occurrence of the neurotoxin, beta-N-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA), in South Florida aquatic food webs[J]. Harmful Algae, 2010, 9(6): 620-635. DOI:10.1016/j.hal.2010.05.002 (  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Jonasson S, Eriksson J, Berntzon L, et al. Transfer of a cyanobacterial neurotoxin within a temperate aquatic ecosystem suggests pathways for human exposure[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of The Unitied States of America, 2010, 107(20): 9252-9257. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0914417107 (  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Réveillon D, Abadie E, Séchet V, et al. β-N-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) and isomers: distribution in different food web compartments of Thau lagoon, French Mediterranean Sea[J]. Marine Environmental Research, 2015, 110: 8-18. DOI:10.1016/j.marenvres.2015.07.015 (  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Masseret E, Banack S, Boumédiène F, et al. Dietary BMAA exposure in an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cluster from southern France[J]. Public Library of Science One, 2013, 8(12): e83406. (  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Réveillon D, Séchet V, Hess P, et al. Systematic detection of BMAA (β-N-methylamino-l-alanine) and DAB (2, 4-diaminobutyric acid) in mollusks collected in shellfish production areas along the French coasts[J]. Toxicon, 2016, 110: 35-46. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.11.011 (  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Al-Sammak M, Hoagland K, Cassada D, et al. Co-occurrence of the cyanotoxins BMAA, DABA and anatoxin-a in nebraska reservoirs, fish, and aquatic plants[J]. Toxins, 2014, 6(2): 488-508. DOI:10.3390/toxins6020488 (  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Cox P A, Banack S A, Murch S J. Biomagnification of cyanobacterial neurotoxins and neurodegenerative disease among the chamorro people of Guam[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of The Unitied States of America, 2003, 100(23): 13380-13383. DOI:10.1073/pnas.2235808100 (  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Wang C, Yan C, Qiu J, et al. Food web biomagnification of the neurotoxin β-N-methylamino-L-alanine in a diatom-dominated marine ecosystem in China[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020, 404: 124217. (  0) 0) |

| [49] |

Lage S, Annadotter H, Rasmussen U, et al. Biotransfer of β-N-Methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) in a eutrophicated freshwater lake[J]. Marine Drugs, 2015, 13(3): 1185-1201. DOI:10.3390/md13031185 (  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Jiao Y, Chen Q, Chen X, et al. Occurrence and transfer of a cyanobacterial neurotoxin β-methylamino-l-alanine within the aquatic food webs of Gonghu Bay (Lake Taihu, China) to evaluate the potential human health risk[J]. Science of The Total Environment, 2014, 468-469: 457-463. (  0) 0) |

| [51] |

陈咏梅, 赵以军, 陈默, 等. 武汉官桥湖蓝藻毒素BMAA的生物累积与健康风险评估[J]. 水生态学杂志, 2019, 40(4): 22-29. Chen Y, Zhao Y, Chen M, et al. Bioaccumulation and health risk assessment of the cyanobacterial neurotoxin BMAA in Guanqiao Lake, Wuhan[J]. Journal of Hydroecology, 2019, 40(4): 22-29. DOI:10.15928/j.1674-3075.2019.04.004 (  0) 0) |

| [52] |

Esterhuizen M, Downing T G. β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in novel South African cyanobacterial isolates[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safaty, 2008, 71: 309-313. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2008.04.010 (  0) 0) |

| [53] |

Esterhuizen M, Downing S, Downing T. G.. Improved sensitivity using liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for detection of propyl chloroformate derivatised β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in cyanobacteria[J]. Water Safety, 2011, 37(2): 133-138. (  0) 0) |

| [54] |

焦一滢. 蓝藻神经毒素β-N-甲氨基-L-丙氨酸在太湖食物链中赋存与环境行为研究[D]. 南京: 南京大学, 2014. Jiao Y. Occurrence of the Cyanobacterial Neurotoxin β-N-methylamino-L-alanine in Foodchains of Lake Tai and the Study of Environmental Fates[D]. Nanjing: Nanjing University, 2014. (  0) 0) |

| [55] |

Rosa C, Cianca C, Mafalda S, et al. The non-protein amino acid b-N-methylamino-L-alanine in Portuguese cyanobacterial isolates[J]. Amino Acids, 2012, 42: 2473-2479. DOI:10.1007/s00726-011-1057-1 (  0) 0) |

| [56] |

Faassen J, Gillissen G, Lurling M. A comparative study on three analytical methods for the determination of the neurotoxin BMAA in cyanobacteria[J]. Public Library of Science One, 2012, 7(5): e36667. (  0) 0) |

| [57] |

Zguna N, Karlson A M L, Ilag L L, et al. Insufficient evidence for BMAA transfer in the pelagic and benthic food webs in the Baltic Sea[J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9(1): 10406. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-46815-3 (  0) 0) |

| [58] |

Banack S A, Cox P A. Biomagnification of cycad neurotoxins in flying foxes[J]. Neurology, 2003, 61: 387-389. DOI:10.1212/01.WNL.0000078320.18564.9F (  0) 0) |

| [59] |

Krüger T, Mönch B, Oppenhäuser S, et al. LC-MS/MS determination of the isomeric neurotoxins BMAA (β-N-methylamino-l-alanine) and DAB (2, 4-diaminobutyric acid) in cyanobacteria and seeds of Cycas revoluta and Lathyrus latifolius[J]. Toxicon, 2010, 55(2-3): 547-557. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.10.009 (  0) 0) |

| [60] |

Faassen E. Presence of the neurotoxin BMAA in aquatic ecosystems: what do we really know?[J]. Toxins, 2014, 6(3): 1109-1138. DOI:10.3390/toxins6031109 (  0) 0) |

| [61] |

Banack S A, Metcalf J S, Spá il Z, et al. Distinguishing the cyanobacterial neurotoxin β-N-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) from other diamino acids[J]. Toxicon, 2011, 57(5): 730-738. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.02.005 (  0) 0) |

| [62] |

Curtis D R, Watkins J C. The excitation and depression of spinal neurones by structurally related amino acids[J]. Journal of Neuronchemistry, 1960, 6: 117-141. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1960.tb13458.x (  0) 0) |

| [63] |

Shaw P J. Molecular and cellular pathways of neurodegeneration in motor neurone disease[J]. Journal of Neuronchemistry, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 2005, 76: 1046-1057. (  0) 0) |

| [64] |

Strong M J, Kesavapany S, Pant H C. The pathobiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A proteinopathy?[J]. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 2005, 64(8): 649-664. DOI:10.1097/01.jnen.0000173889.71434.ea (  0) 0) |

| [65] |

Cozzolino M, Ferri A, Teresa Carrì M. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: from current developments in the laboratory to clinical implications[J]. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 2008, 10(3): 405-444. (  0) 0) |

| [66] |

Boillee S, Vande V C, Cleveland D W. ALS: A disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors[J]. Neuron, 2006, 52(1): 39-59. DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.018 (  0) 0) |

| [67] |

Majoor-Krakauer D, Willems P J, Hofman A. Genetic epidemiology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis[Z]. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

(  0) 0) |

| [68] |

Nunn P B, Seelig M, Zagoren J C, et al. Stereospecific acute neuronotoxicity of 'uncommon' plant amino acids linked to human motor-system diseases[J]. Brain Research, 1987, 410(2): 375. DOI:10.1016/0006-8993(87)90342-8 (  0) 0) |

| [69] |

Lipton S A. Failures and successes of NMDA receptor antagonists: Molecular basis for the use of open-channel blockers like memantine in the treatment of acute and chronic neurologic insults[J]. NeuroRx, 2004, 1(1): 101-110. DOI:10.1602/neurorx.1.1.101 (  0) 0) |

| [70] |

Weiss J H, Choi D W. β-N-methylamino-L-alanine neurotoxicity: Requirement for bicarbonate as a cofactor[J]. Science, 1988, 241(4868): 973-975. DOI:10.1126/science.3136549 (  0) 0) |

| [71] |

Copani A, Canonico P L, Catania M V, et al. Interaction between β-N-methylamino-L-alanine and excitatory amino acid receptors in brain slices and neuronal cultures[J]. Brain Research, 1991, 558(1): 79-86. DOI:10.1016/0006-8993(91)90716-9 (  0) 0) |

| [72] |

Nedeljkov V, Lopičić S, Pavlović D, et al. Electrophysiological effect of β-N-Methylamino-L-alanine on retzius nerve cells of the leech Haemopis sanguisuga[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2005, 1048(1): 349-351. DOI:10.1196/annals.1342.034 (  0) 0) |

| [73] |

Lopicic S, Nedeljkov V, Cemerikic D. Augmentation and ionic mechanism of effect of β-N-methylamino-l-alanine in presence of bicarbonate on membrane potential of Retzius nerve cells of the leech Haemopis sanguisuga[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 2009, 153(3): 284-292. (  0) 0) |

| [74] |

Cucchiaroni M L, Viscomi M T, Bernardi G, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 mediates the electrophysiological and toxic actions of the cycad derivative β-N-methylamino-L-alanine on substantia nigra pars compacta daergic neurons[J]. Journal of Neuroscience, 2010, 30(15): 5176-5188. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5351-09.2010 (  0) 0) |

| [75] |

Seawright A A, Brown A W, Nolan C C, et al. Selective degeneration of cerebellar cortical neurons caused by cycad neurotoxin, L-beta-methylaminoalanine (L-BMAA), in rats[J]. Neuropathology and Applie Neurobiology, 1990, 16(2): 153-169. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2990.1990.tb00944.x (  0) 0) |

| [76] |

Smith S E, Meldrumm B S. Receptor site specificity for the acute efffects of fl-N-methylamino-alanine in mice[J]. European Journal of Pharmacology, 1990, 187: 131-134. DOI:10.1016/0014-2999(90)90350-F (  0) 0) |

| [77] |

Lindstrom H, Luthman J, Mouton P, et al. Plant-derived neurotoxic amino acids (beta-N-oxalylamino-L-alanine and beta-N-methylamino-L-alanine): Effects on central monoamine neurons[J]. Journal of Neurochemistry, 1990, 55(3): 941-949. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04582.x (  0) 0) |

| [78] |

Matsuoka Y, Rakonczay Z, Giacobini E, et al. L-β-methylamino-alanine-induced behavioral changes in rats[J]. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 1993, 44: 727-734. DOI:10.1016/0091-3057(93)90191-U (  0) 0) |

| [79] |

Rakonczay Z, Matsuoka Y, Giacobini E. Effects of L-β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (L-BMAA) on the cortical cholinergic and glutamatergic systems of the rat[J]. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 1991, 29: 121-126. DOI:10.1002/jnr.490290114 (  0) 0) |

| [80] |

Liu X, Rush T, Zapata J, et al. β-N-methylamino-l-alanine induces oxidative stress and glutamate release through action on system Xc-[J]. Experimental Neurology, 2009, 217(2): 429-433. DOI:10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.002 (  0) 0) |

| [81] |

Fogal B, Li J, Lobner D, et al. System Xc- activity and astrocytes are necessary for interleukin-1 -mediated hypoxic neuronal injury[J]. Journal of Neuroscience, 2007, 27(38): 10094-10105. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2459-07.2007 (  0) 0) |

| [82] |

Piani D, Fontana A. Involvement of the cystine transport system Xc- in the macrophage-induced glutamate-dependent cytotoxicity to neurons[J]. The Journal of Immunology, 1994, 152(7): 3578-3585. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.152.7.3578 (  0) 0) |

| [83] |

Murch S J, Cox P A, Banack S A, et al. Occurrence of beta-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) in ALS/PDC patients from Guam[J]. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 2004, 110(4): 267-269. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00320.x (  0) 0) |

| [84] |

Glover W B, Mash D C, Murch S J. The natural non-protein amino acid N-β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) is incorporated into protein during synthesis[J]. Amino Acids, 2014, 46(11): 2553-2559. DOI:10.1007/s00726-014-1812-1 (  0) 0) |

| [85] |

Dunlop R A, Cox P A, Banack S A, et al. The non-protein amino acid BMAA is misincorporated into human proteins in place of L-serine causing protein misfolding and aggregation[J]. Public Library of Science One, 2013, 8(9): e75376. (  0) 0) |

| [86] |

Murch S J, Cox P A, Banack S A. A Mechanism for slow release of biomagnified cyanobacterial neurotoxins and neurodegenerative disease in Guam[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of The Unitied States of America, 2004, 101(33): 12228-12231. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0404926101 (  0) 0) |

| [87] |

Santucci S, Zsurger N, Chabry J. β-N-methylamino-L-alanine induced in vivo retinal cell death[J]. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2009, 109: 819-825. DOI:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06022.x (  0) 0) |

| [88] |

Okle O, Stemmer K, Deschl U, et al. L-BMAA induced ER stress and enhanced caspase 12 cleavage in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells at low nonexcitotoxic concentrations[J]. Toxicological Sciences, 2013, 131(1): 217-224. DOI:10.1093/toxsci/kfs291 (  0) 0) |

| [89] |

Karlsson O, Kultima K, Wadensten H, et al. Neurotoxin-induced neuropeptide perturbations in striatum of neonatal rats[J]. Journal of Proteome Research, 2013, 12(4): 1678-1690. DOI:10.1021/pr3010265 (  0) 0) |

| [90] |

Lobner D, Piana P M T, Salous A K, et al. β-N-methylamino-L-alanine enhances neurotoxicity through multiple mechanisms[J]. Neurobiology of Disease, 2007, 25(2): 360-366. DOI:10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.002 (  0) 0) |

| [91] |

Karlsson O, Berg A L, Lindstrom A K, et al. Neonatal exposure to the cyanobacterial toxin BMAA induces changes in protein expression, and neurodegeneration in adult Hippocampus[J]. Toxicological Sciences, 2012, 130(2): 391-404. DOI:10.1093/toxsci/kfs241 (  0) 0) |

| [92] |

Wilson K M, Burkus-Matesevac A, Maddox S W, et al. Native ubiquitin structural changes resulting from complexation with β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA)[J]. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 2021, 32(4): 895-900. DOI:10.1021/jasms.0c00372 (  0) 0) |

| [93] |

Zecca L, Zucca F A, Wilms H, et al. Neuromelanin of the substantia nigra: a neuronal black hole with protective and toxic characteristics[J]. Trends Neurosci, 2003, 26(11): 578-580. DOI:10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.009 (  0) 0) |

| [94] |

D'amato R J, Lipman Z P, Snyder S H. Selectivity of the parkinsonian neurotoxin MPTP: Toxic metabolite MPP+ binds to neuromelanin[J]. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science), 1986, 231(4741): 987-989. DOI:10.1126/science.3080808 (  0) 0) |

| [95] |

Jimbow K. Current update and trends in melanin pigmentation and melanin biology[J]. The Keio Journal of Medicine, 1995, 44(1): 9-18. DOI:10.2302/kjm.44.9 (  0) 0) |

| [96] |

McManus M J, Murphy M P, Franklin J L. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant mitoo prevents loss of spatial memory retention and early neuropathology in a transgenic mouse model of alzheimer's disease[J]. Journal of Neuroscience, 2011, 31(44): 15703-15715. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0552-11.2011 (  0) 0) |

| [97] |

Lastres-Becker I, Ulusoy A, Innamorato N G, et al. α-Synuclein expression and Nrf2 deficiency cooperate to aggravate protein aggregation, neuronal death and inflammation in early-stage Parkinson's disease[J]. Human Molecular Genetics, 2012, 21(14): 3173-3192. DOI:10.1093/hmg/dds143 (  0) 0) |

| [98] |

Dariani S, Baluchnejadmojarad T, Roghani M. Thymoquinone attenuates astrogliosis, neurodegeneration, mossy fiber sprouting, and oxidative stress in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy[J]. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, 2013, 51(3): 679-686. DOI:10.1007/s12031-013-0043-3 (  0) 0) |

| [99] |

An T, Shi P, Duan W, et al. Oxidative stress and autophagic alteration in brainstem of SOD1-G93A mouse model of ALS[J]. Molecular Neurobiology, 2014, 49(3): 1435-1448. DOI:10.1007/s12035-013-8623-3 (  0) 0) |

| [100] |

Eleuteri S, Di Giovanni S, Rockenstein E, et al. Novel therapeutic strategy for neurodegeneration by blocking a seeding mediated aggregation in models of Alzheimer's disease[J]. Neurobiology of Disease, 2015, 74: 144-157. DOI:10.1016/j.nbd.2014.08.017 (  0) 0) |

| [101] |

Delcourt N, Claudepierre T, Maignien T, et al. Cellular and molecular aspects of the β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) mode of action within the neurodegenerative pathway: facts and controversy[J]. Toxins, 2018, 10(1): 6. (  0) 0) |

| [102] |

Murch S J, Cox P A, Banack S A, et al. Occurrence of beta-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in ALS/PDC patients from Guam[J]. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 2004, 110(4): 267-269. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00320.x (  0) 0) |

| [103] |

Marie A, Oskar K, Ulrika B, et al. Maternal transfer of the cyanobacterial neurotoxin β-N- methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) via milk to suckling offspring[J]. Public Library of Science One, 2013, 10(7): e0133110.. (  0) 0) |

| [104] |

Marie A, Oskar K, Sandra A B, et al. Transfer of developmental neurotoxin β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) via milk to nursed offspring: Studies by mass spectrometry and image analysis[J]. Toxicology Letters, 2016, 258: 108-114. DOI:10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.06.015 (  0) 0) |

| [105] |

Andersson M, Ersson L, Brandt I, et al. Potential transfer of neurotoxic amino acid β-N-methylamino-alanine (BMAA) from mother to infant during breast-feeding: Predictions from human cell lines[J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2017, 320: 40-50. DOI:10.1016/j.taap.2017.02.004 (  0) 0) |

| [106] |

Andersson M, Karlsson O, Brandt I. The environmental neurotoxin β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (L-BMAA) is deposited into birds' eggs[J]. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2018, 147: 720-724. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.09.032 (  0) 0) |

| [107] |

Banack S A, Murch S J, Cox P A. Neurotoxic flying foxes as dietary items for the Chamorro people, Marianas Islands[J]. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2006, 106(1): 97-104. DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2005.12.032 (  0) 0) |

| [108] |

Vega A, Bell E A, Nunn P B. The preparation of L-and D-α-amino-β-methylaminopropionic acids and the identification of the compound isolated from cycas circinalis as the L-isomer[J]. Phytochemistry, 1968, 7: 1885-1887. DOI:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)86667-4 (  0) 0) |

| [109] |

Ross S M, Spencer P S. Specific antagonism of behavioral action of "uncommon" amino acids linked to motor-system diseases[J]. Synapse, 1987, 1(3): 248-253. DOI:10.1002/syn.890010305 (  0) 0) |

| [110] |

Karlsson O, Lindquist N G, Brittebo E B, et al. Selective brain uptake and behavioral effects of the cyanobacterial toxin BMAA (β-N-Methylamino-L-alanine) following Neonatal Administration to Rodents[J]. Toxicological Sciences, 2009, 109(2): 286-295. DOI:10.1093/toxsci/kfp062 (  0) 0) |

| [111] |

Cox P A, Davis D A, Mash D C, et al. Do vervets and macaques respond differently to BMAA?[J]. Neurotoxicology, 2017, 57: 310-311. (  0) 0) |

| [112] |

Spencer P S, Nunn P B, Hugon J, et al. Guam amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-parkinsonism-dementia linked to a plant excitant neurotoxin[J]. Science, 1987, 237(4814): 517-522. DOI:10.1126/science.3603037 (  0) 0) |

| [113] |

Dawson R JR, Marschall E G, Chan K C, et al. Neurochemical and neurobehavioral effects of neonatal administration of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine and 3, 3-Iminodipropionitrile[J]. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 1998, 20(2): 181-192. DOI:10.1016/S0892-0362(97)00078-0 (  0) 0) |

| [114] |

Cruz-Aguado R, Winkler D, Shaw C A. Lack of behavioral and neuropathological effects of dietary β-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in mice[J]. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 2006, 84(2): 294-299. DOI:10.1016/j.pbb.2006.05.012 (  0) 0) |

| [115] |

Perry T S, Bergeron Catherine, Biro A J, et al. β-N-Methylamino-L-alanine: Chronic oral administration is not neurotoxic to mice[J]. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 1989, 94(1-3): 173-180. DOI:10.1016/0022-510X(89)90227-X (  0) 0) |

2. The Key Laboratory of Marine Environment and Ecology, Ministry of Education, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China

2023, Vol. 53

2023, Vol. 53