2. 武汉大学人民医院 神经外科 湖北 武汉 430060

2. Dept.of neurosurgery, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan 430060, China

良性持发性眼睑痉挛 (benign essential blepharospasm, BEB) 是一种特发性功能障碍,以双侧眼睑不自主痉挛,干扰视觉功能和导致眼部不适为特征,属于局灶性肌张力障碍[1]。各国报道的眼睑痉挛发病率稍有差异,约为1/20 000[2]。大部分病例为散发,约20%-30%的病例有家族史[3]。欧美流行病学调查示女性患病率是男性的2.3倍[4]。我国尚无相关的流行病学资料。

BEB大部分在50岁以后起病,相对于男性,女性发病年龄晚4.7年[5]。早期表现为瞬目增多,一些患者始发症状为单眼,但随着病情的发展会逐渐累及双侧眼睑。晚期可出现持续闭眼甚至功能盲 (functional blindness),严重影响患者日常生活及社交活动。部分患者可合并口下颌肌张力障碍,进展为颅颈肌张力障碍或称Meige综合征[6]。大多数患者伴随焦虑和抑郁,给患者带来极大的困扰。BEB患者与面肌痉挛临床症状相似,但强迫观念的发生率明显高于面肌痉挛,推测强迫观念可能与基底节区功能失调有关[7]。

BEB的病因和病理生理机制尚不明确,临床上也尚无治愈的方法[8, 9]。有些BEB患者呈家族性发病,虽然尚未确定致病基因[10]。已有学者在眼睑痉挛家系中对DYT1等肌张力障碍相关基因进行检测,但均未发现有明确致病基因[11]。

因此,我们对20例BEB患者进行基因检测,其中包括与肌张力障碍、发作性共济失调 (episodic ataxia,EA)、发作性运动诱发性运动障碍 (paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesias,PKD)、发作性非运动诱发性运动障碍 (paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesias,PNKD)、特发性震颤 (essential tremor,ET) 和帕金森病相关的基因,以及ADCK3、AFG3L2和ANO10等共151种基因,并分析临床表现与基因突变的关系。

1 资料与方法 1.1 临床资料2015年4月至2015年10月在武汉大学人民医院神经内科运动障碍专病门诊就诊的BEB患者共20例。纳入标准:①年龄为18-80岁。②BEB患者诊断符合BEB的诊断标准,可合并相邻部位的肌张力障碍,如颅颈肌张力障碍/Meige综合征,头颅CT/MRI未显示脑实质异常。③除眼睑痉挛及相邻部位肌张力障碍外,无其他神经系统症状和体征,无多发性硬化、帕金森病等其它神经系统疾病或继发性眼睑痉挛。④所有患者经知情同意。

1.2 研究方法 1.2.1 患者一般情况调查对这20例BEB患者进行病史记录、神经系统检查和调查问卷 (见表 2)。调查内容主要包括如下:①一般情况、病史摘要、发病时间、发病年龄、首发部位、感觉诡计、首次就诊时间、首次确诊时间、血压等。②治疗情况:开始服药时间、剂量、是否有效、停药原因等。③往史和家族史:高血压、糖尿病、心脏病、甲亢、麻疹、脑血管病、脑外伤、脑炎、眼部疾病等。④危险/保护因素调查:包括杀虫剂、除草剂、防腐剂、重金属、氰化物、化学稀释剂、有机溶剂、工作废气毒物、化工产品、钢筋、水泥、合成树脂、生活区工厂、居住环境、吸烟饮酒、饮茶、咖啡、药物滥用、雌激素类药物、体育锻炼、膳食、饮水等情况。

1.2.2 基因检测在患者知情同意的情况下,抽取静脉血3-5 ml。采用二代测序方法,检测可能导致运动障碍临床表现各类疾病的相关基因共151种 (表 1);具体包括文库构建、杂交捕获、上机测序和生物信息分析。生物信息分析包括Bascalling、Align分析、SNP分析、DIP分析、蛋白质损伤分析和SNP-DIP-Poly综合分析。

| 表 1 所检测的相关基因 |

| 表 2 20例BEB患者的临床一般资料和突变基因 |

|

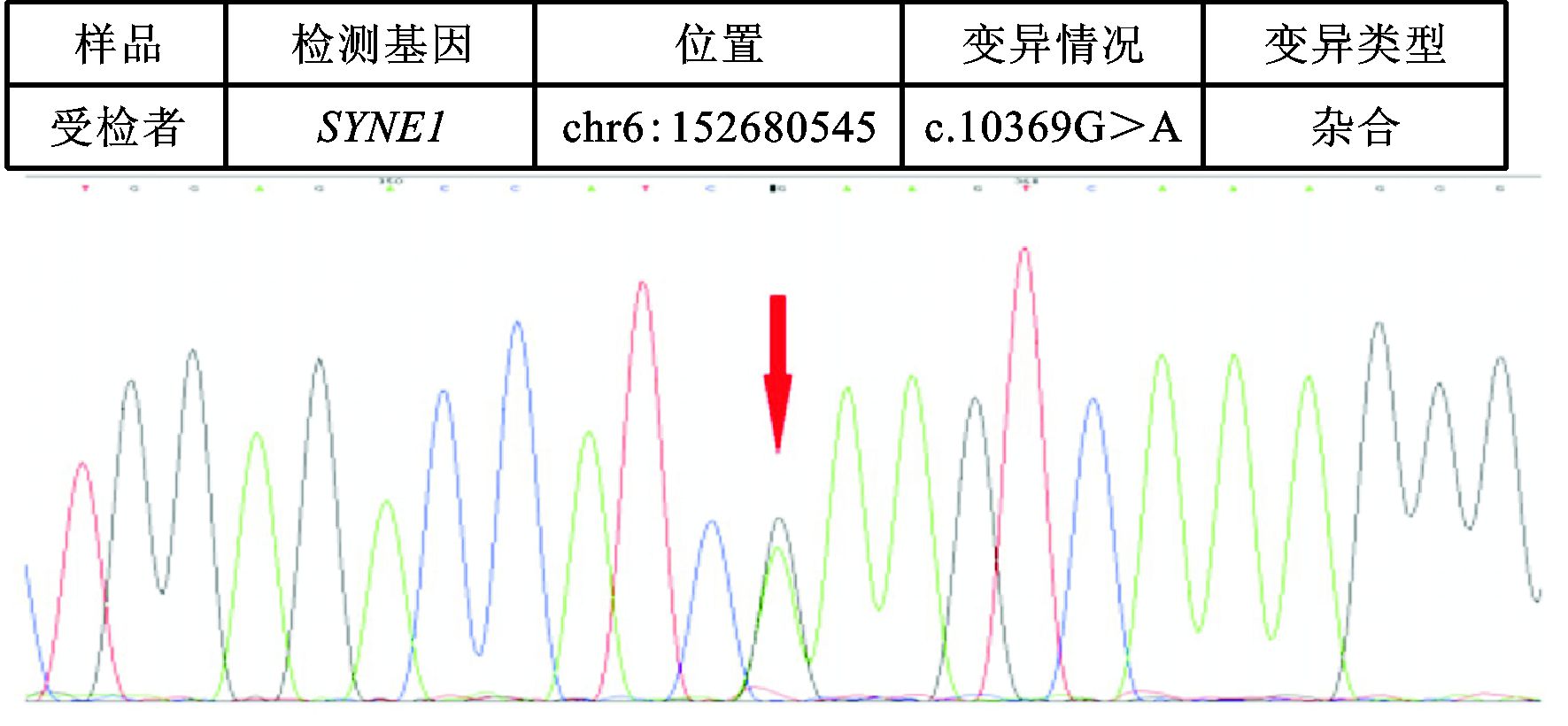

图 1 突变的SYNE1基因 (7例患者) |

|

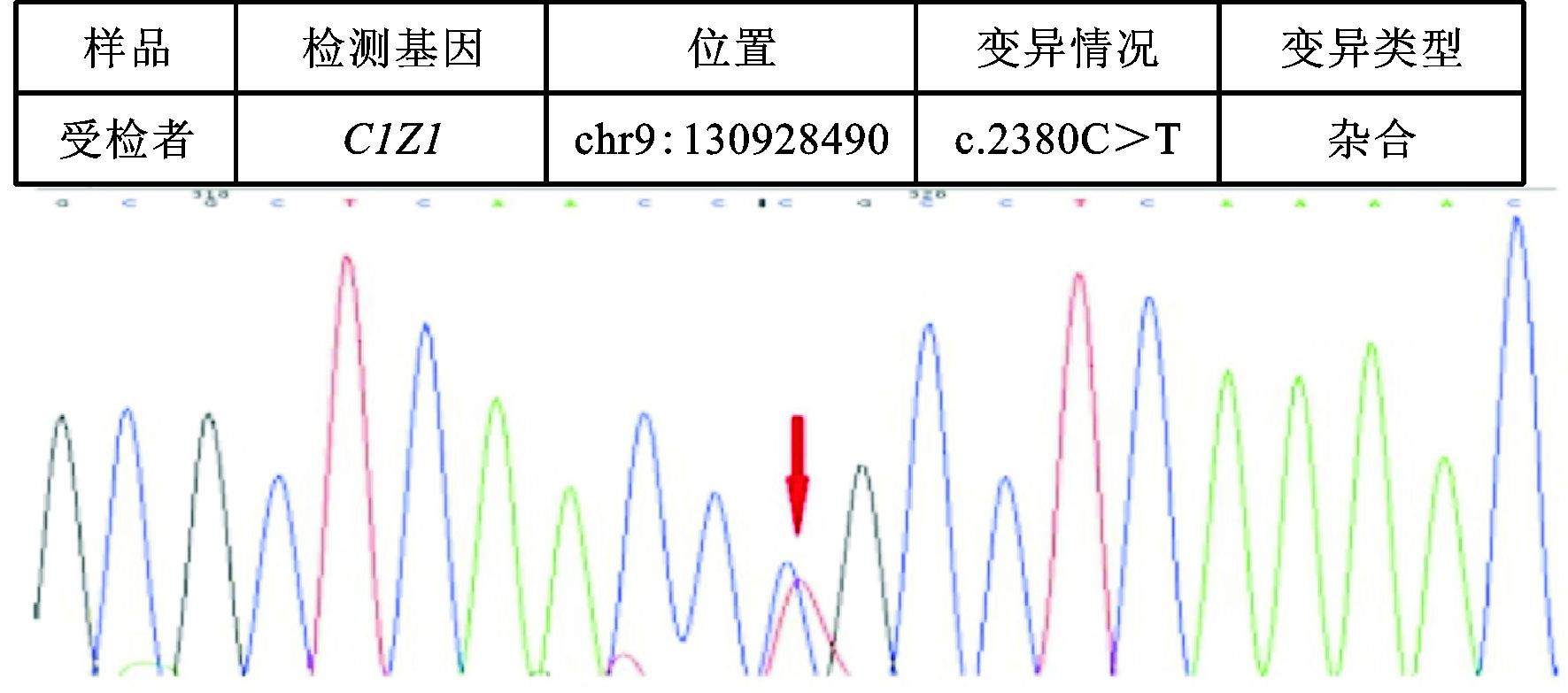

图 2 突变的CIZ1基因 (2例患者) |

20例患者中,男3例、女17例,平均年龄55.25(31-72) 岁,病程平均6.15(1-24) 年。

2.1.2 首发症状睁眼费劲9例,频繁眨眼7例,双眼无力2例,眼睑抽动2例。

2.1.3 就诊过程和确诊时间首诊科室眼科13例,神经内科5例,大内科2例;从首次就诊到确诊,平均去过3家医院。从发病时间到确诊时间平均为4.11年,其中最长者15年。

2.1.4 既往病史一氧化碳中毒史1例,高血压病史2例,同时有高血压病、糖尿病、脑血管病和卵巢摘除术史1例;其余患者否认其他疾病史。

2.1.5 危险/保护因素吸烟史2例,饮酒史3例,接触杀虫剂/除草剂5例,饮茶史4例,接触水泥史2例,接触过猪疫苗1例,用过雌激素类药物史1例。

2.2 基因检测所见20例BEB患者中,有家族史者2例。

未发现上述151种基因中任何一种突变者2例;检测出两种基因突变者7例;SYNE1基因突变7例 (图 1),CIZ1基因突变2例 (图 2),CACNA1A基因突变2例,LRRK2基因突变2例,FUS基因突变2例;C10orf2、TPP1、SLC1A3、PNKD、EIF4G1、SETX、PRRT2、SPTBN2和TTBK2基因突变者各1例 (见表 2)。

3 讨论眼睑痉挛的病因和发病机制尚不清楚[12],大部分学者认为该病发病机制可能与脑部基底节损害、黑质-纹状体GABA能神经元、多巴胺、胆碱能等神经递质失调有关[13-15]。改变体内多巴胺的水平或特定多巴胺受体的功能,可以为眼睑痉挛创造诱发条件。Karimi等[15]利用D2受体选择性更高的放射性配体18F N-甲基-苯呱利多 (NMB) 和亲和性最小的5-羟色胺2A发现,局灶性肌张力障碍患者壳核内NMB含量并没有下降,这表明与眼睑痉挛有关的可能是多巴胺D3受体而不是D2受体。还有一些研究[14]表明,肌张力障碍患者感觉皮层和纹状体的GABA水平显著降低,说明GABA也参与了其病理生理过程。“二次打击”学说认为,患者有易感的基因为大脑功能异常创造了条件,再加上可能的环境触发,从而引起了肌张力障碍行为[16-18]。一些有关瞬目反射的研究提示,基底节功能失调可能导致脑干中间神经元的兴奋性增高,从而引起眼睑痉挛[17]。还有研究认为,肌张力障碍是由于患者异常的大脑重塑和运动区出现环路抑制造成的[18]。

眼睑痉挛发病的前5年内,肌张力障碍常可波及相邻部位[19]。有些眼睑痉挛患者发病呈家族性,但目前研究未能确定任何致病基因。许多证据都支持BEB的发病很可能与遗传有关。Clarimon等人[20]对意大利和北美两个眼睑痉挛家系进行了DRD5和DYT1检测,结果是阴性。Xiromerisiou等人[21]对一个希腊的眼睑痉挛家系进行了THAP1基因检测,发现在眼睑痉挛THAP1突变是罕见的,但对于眼睑痉挛来说需要进行基因筛查,尤其是有阳性家族史的时候。对于调查突变引起的功能性改变,进一步的基因型和表型的相关性研究是至关重要的。Defazio等人[22]对56例先证者的家系的遗传模式进行研究,发现其27%的一级亲属患BEB或其它局灶性肌张力障碍,高度提示其具有遗传易感性。在此前他们报道了两个意大利家系发现其遗传模式可能为常染色体显性遗传,但检测已知的肌张力障碍相关基因DYT1、DYT6、DYT7和DYT13均阴性,推测眼睑痉挛可能是由于其它未被发现的基因所致。

总而言之,目前的证据都显示,眼睑痉挛是由于存在易感基因再加上环境触发而引起[23]。

我们在这20例患者中发现有2例CIZ1突变。为了寻找p21Cip1/Waf1结合蛋白,在这个过程中发现了一个未知蛋白后来命名为CIZ1,即Cip1-相互作用的锌指蛋白[24]。CIZ1基因在人类定位在9q34,包括一个38 kb的DNA片段。当p21Cip1/Waf1和CIZ1分别被过表达时,它们都在细胞核中。然而当将之转染到细胞中,二者从细胞核易位到细胞质[24]。CIZ1也显示出DNA结合活性和作为转录因子的共活化剂[25]。基于这些研究,CIZ1的功能像一个“调解员”,即细胞周期进程中桥梁细胞的周期调控作用。最近,发现在人和小鼠CIZ1基因各种突变,导致各种模式的蛋白质产物中的氨基酸残基异常。近日,CIZ1报道与阿尔茨海默氏病[26]、肌张力障碍[27]以及类风湿关节炎[28]有关。此外,在许多恶性肿瘤包括肺癌[29]、尤文氏瘤[30]、结肠癌[31]、胆囊癌[32]、前列腺癌[33]和乳腺癌[25]中观察到CIZ1的表达升高。

肌张力障碍疾病可以由单基因突变引起[34]。CIZ1基因突变是与肌张力障碍相关的。CIZ1基因外显子7中A突变为G,导致替换为S264G,在一个遗传性颈肌张力障碍的家系中,5个家庭成员通过外显子组测序发现了这一突变。这一点突变不仅改变CIZ1的mRNA的连接模式,也改变了其在细胞核的位置。这一突变使细胞核分裂成更少但更大的组分,从而影响了CIZ1的生物学功能。

既然CIZ1与肌张力障碍疾病有关,CIZ1与其它许多蛋白质结合,发挥其DNA复制、细胞周期调控的作用,影响着病病的发展。CIZ1的失调或突变已揭示其在肌张力障碍中有重要作用,意味着其可以考虑作为诊断生物标志物或治疗靶。而眼睑痉挛是肌张力障碍疾病的一种,CIZ1又能否影响眼睑痉挛的发生发展,目前尚未有人研究,均有待进一步研究。

在我们的20例患者中,发现有7例SYNE1基因突变,均为错义突变。SYNE1基因编码nesprin-1蛋白[35],是以多个膜收缩蛋白重复为特点和在横纹肌中高表达。肌动球蛋白张力通过Nesprin-1作用于细胞核,从而影响内皮细胞黏附、迁移和循环应变诱导的重新定位。在骨骼肌,Nesprin-1和被认为是连接细胞核和细胞骨架网络的桥梁。Nesprin-1和肌间线蛋白的破坏可以导致核锚地缺陷和骨骼肌纤维化。由于Nesprin中包含KASH结构域,因此也会影响LINC复合体的形成,进而失去细胞核骨架与细胞骨架之间的联系,导致进行性肌营养不良。

SYNE1突变除了会导致常染色体显性遗传Emery-Dreifuss肌营养不良 (AD-EDMD)4型[36],还会引起脊髓小脑共济失调8型[37]、肌源性多发性关节挛缩症伴Emery-Dreifuss肌营养不良[38]、智力障碍、痉挛性截瘫和轴突性神经病。还有报道会引起显著的肌肉萎缩[39]。有报道称SYNE1与神经肌肉接头功能有关[40]。还有人研究得出SYNE1变异与月经性偏头痛有关[41]。在体内和体外试验中显示,Nesprin-1在间充质干细胞向心肌样细胞分化起关键作用[42]。Nesprin-1在间充质干细胞的增殖和细胞凋亡中起重要作用[43]。

还有报道称,SYNE1与双相情感障碍和复发性抑郁症有关[44]。有确凿的证据表明,双相情感障碍有遗传易感性。英国的精神病全基因组关联分析和双相情感障碍工作组联合做了一项研究,入选了1 527例双相情感障碍患者和1 579例正常对照,以及1 159例复发性单相抑郁症和2 592例正常对照,结果发现,SYNE1与双相情感障碍和复发性单相抑郁症的易感性有关。

我们在这20例患者中,发现有2例CACNA1A基因突变。CACNA1C基因位于12p13.3,由44个外显子和6个可选择性的外显子组成,是一种编码L型电压门控钙通道 (LTCC) 的亚单位的基因。具有广泛的mRNA剪接功能[45],可能和杏仁核的结构和功能有关,且有人研究发现与CACNA1C基因相关的杏仁核结构和功能的差异主要表现在青春期。Cavl.2是LTCC的主要组成部分,介导钙离子进入细胞内,在记忆形成、学习和行为中、神经元存活、树突发育、突触可塑性等方面起着关键作用[46]。

Sklart[47]等GWAS研究的结果提示CACNA1C基因与双相障碍明显相关。CACNA1C基因型除了与双相障碍密切相关外,有很多学者发现CACNA1C基因突变是多种精神疾病伴随边缘系统功能障碍的危险因素,包括精神分裂症、抑郁症[48]。有学者通过研究发现CACNA1C基因可能与以QT间期延长间隔肥厚型心肌病、先天性心脏缺陷和心源性猝死为特征的心脏疾病有关[49]。

在我们20例患者中,有2例LRRK2基因突变。LRRK2又名Park8,是大分子蛋白,长约144 kb,位于第12号染色体,p11.2-13.1,编码2 527个氨基酸。LRRK2在中枢神经系统高度表达,参与蛋白质的结合、相互作用,以及参与蛋白质运输和信号转导等功能[51]。LRRK2基因突变导致GTP酶的活性下降,改变了其激酶的结构域,从而增加了激酶的活性,随后产生LRRK2毒性。

LRRK2在胶质细胞未发现其表达,只在神经细胞表达。年龄越大LRRK2的表达越多[52]。LRRK2在病理条件下可能参与α-突触核蛋白及Tau蛋白的磷酸化和聚集。LRRK2基因突变是家族性PD的最常见原因,同时其突变也增加患者散发PD的风险,但是有学者研究发现LRRK2基因突变也可能与阿尔茨海默病 (Alzheimer disease,AD) 有关[53]。

还有2例患者发现FUS基因突变。FUS基因,又称为脂肪肉瘤易位基因 (translocation in liposarcoma,TLS),基因位于人类16号染色体16p11.2上,序列高度保守,广泛表达于多种组织[54]。FUS蛋白的功能目前不是十分清楚,但可能涉及维持神经元的可塑性等过程[54]。

FUS基因已被确定为肌萎缩性侧索硬化症 (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,ALS)、特发性震颤和额颞叶变性 (frontotemporal lobe degeneration,FTLD) 的罕见类型的危险因素[55]。此外,FUS蛋白异常聚集已多种神经变性疾病中有报道,包括ALS、FTLD和多聚谷氨酰胺疾病,暗示FUS在这些神经变性疾病的发生发展中起重要作用。FUS基因突变与肌张力障碍疾病之间的关联性,虽然还没有相关报道,但有的FTLD患者是可以伴肌张力障碍表现的[56]。

还有其它的基因突变,例如C10orf2、TPP1、SLC1A3、PNKD、EIF4G1、SETX、PRRT2、SPTBN2、TTBK2。我们分别在pubmed等数据库将这些基因与肌张力障碍 (dystonia) 或眼睑痉挛 (blepharospasm) 进行检索。只有PRRT2基因报道与痉挛性斜颈有关。其余的基因均未见报道与肌张力障碍或眼睑痉挛有关。PRRT2基因是PKD、良性家族性婴儿癫痫和婴儿惊厥伴发作性手足舞蹈徐动征的主要致病基因[57],此外,PRRT2致病突变在PNKD、发作性劳累诱发性运动障碍、家族性偏瘫性偏头痛、发作性共济失调、热性惊厥、婴儿非惊厥性癫痫、夜间癫痫和痉挛性斜颈等疾病中也有发现。

其他的基因查阅信息如下。据报道C10orf2基因突变与多个线粒体DNA缺失、慢性进行性眼外肌麻痹和早衰有关[58]。TPP1是重要的端粒酶及端粒长度的负性调控因子[59]。有报道,在孤立性儿童起病的进行性共济失调,TPP1缺陷为罕见病因[60]。还有报道称,TPP1基因突变可导致晚期婴儿型神经元蜡样脂褐质沉积症[61]。SLC1A3基因突变可能与抽动秽语综合征、注意力缺失/多动症有关[62]。PNKD基因突变与发作性非运动诱发性运动障碍有关[63]。2011年在法国一个PD家系中发现EIF4G1基因突变,之后很多学者进行了验证研究,有很多阴性结果,因而对EIF4G1基因与PD的关系有争议[64]。SETX基因突变与共济失调伴眼球运动障碍2型、幼年和成年发病小脑共济失调、舞蹈病和运动神经元病有关[65]。SPTBN2与脊髓小脑共济失调5型有关[66]。TTBK2与脊髓小脑共济失调11型有关[67]。

综上所述,我们认为CIZ1和SYNE1基因突变与眼睑痉挛的关系最密切。而且我们20例患者中有2例患者有家族史,正是这两例患者,分别测出CIZ1基因突变和SYNE1基因突变。另外,CIZ1基因突变在痉挛性斜颈家系中有报道。眼睑痉挛和痉挛性斜颈都属于肌张力障碍疾病,而且有时二者在同一个患者身上出现。我们推测CIZ1基因突变可能与眼睑痉挛有关,需要更进一步做大样本研究或家系研究。而SYNE1基因突变目前还没有报道与肌张力障碍或眼睑痉挛有关,但SYNE1基因在横纹肌中高表达,且对肌肉萎缩、肌营养不良、神经肌肉接头、运动神经元的支配中起着重要的作用。同时据报道SYNE1基因与双相情感障碍和复发性抑郁症有关,而在BEB患者中合并焦虑抑郁症状的特别多。在20例BEB患者中检测出7例SYNE1基因突变,这个比例是很大的。我们也需要大样本或家系研究来证实,或在动物实验中探索CIZ1和SYNE1基因在眼睑痉挛中的作用。

| [1] | Lee MS, Johnson M, Harrison AR. Gender differences in benign essential blepharospasm[J]. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, 2012, 28(3): 169-170. DOI: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318244a380. |

| [2] | Hallett M. Blepharospasm:recent advances[J]. Neurology, 2002, 59(9): 1306-1312. DOI: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000027361.73814.0E. |

| [3] | Hallett M, Evinger C, Jankovic J, et al. Update on blepharospasm: report from the BEBRF International Workshop[J]. Neurology, 2008, 71(16): 1275-1282. DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327601.46315.85. |

| [4] | Fernandez HH, Pagan F, Danisi F, et al. Prospective Study Evaluating IncobotulinumtoxinA for Cervical Dystonia or Blepharospasm: Interim Results from the First 145 Subjects with Cervical Dystonia[J]. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov, 2013, 3(16): 285-292. |

| [5] | Macerollo A, Superbo M, Gigante AF, et al. Diagnostic delay in adult-onset dystonia: data from an Italian movement disorder center[J]. J Clin Neurosci, 2015, 22(3): 608-610. DOI: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.09.014. |

| [6] | Jinnah HA, Berardelli A, Comella C, et al. The focal dystonias: current views and challenges for future research[J]. Mov Disord, 2013, 28(7): 926-943. DOI: 10.1002/mds.25567. |

| [7] | Defazio G, Hallett M, Jinnah HA, et al. Development and validation of a clinical scale for rating the severity of?blepharospasm[J]. Mov Disord, 2015, 30(4): 525-530. DOI: 10.1002/mds.26156. |

| [8] | Defazio G, Hallett M, Jinnah HA, et al. Development and validation of a clinical guideline for diagnosing blepharospasm[J]. Neurology, 2013, 81(3): 236-240. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829bfdf6. |

| [9] | Conte A, Defazio G, Ferrazzano G, et al. Is increased blinking a form of blepharospasm[J]. Neurology, 2013, 80(24): 2236-2241. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318296e99d. |

| [10] | Defazio G, Abbruzzese G, Aniello MS, et al. Environmental risk factors and clinical phenotype in familial and sporadic primary blepharospasm[J]. Neurology, 2011, 77(7): 631-637. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182299e13. |

| [11] | Defazio G, Matarin M, Peckham EL, et al. The TOR1A polymorphism rs1182 and the risk of spread in primary blepharospasm[J]. Mov Disord, 2009, 24(4): 613-616. DOI: 10.1002/mds.v24:4. |

| [12] | Martino D, Liuzzi D, Macerollo A, et al. The phenomenology of the geste antagoniste in primary blepharospasm and cervical dystonia[J]. Mov Disord, 2010, 25(4): 407-412. DOI: 10.1002/mds.23011. |

| [13] | Fayers T, Shaw SR, Hau SC, et al. Changes in corneal aesthesiometry and the sub-basal nerve plexus in benign essential blepharospasm[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2015, 99(11): 1509-1513. DOI: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306426. |

| [14] | Evinger C. Benign essential blepharospasm is a disorder of neuroplasticity: lessons from animal models[J]. J Neuroophthalmol, 2015, 35(4): 374-379. DOI: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000317. |

| [15] | Karimi M, Moerlein SM, Videen TO, et al. Decreased striatal dopamine receptor binding in primary focal dystonia: a D2 or D3 defect[J]. Mov Disord, 2011, 26(1): 100-106. DOI: 10.1002/mds.23401. |

| [16] | Pardal-Fernández JM, Mansilla-Lozano D. Value of simultaneous electromyographic recording of the levator palpebrae and the orbicularis oculi muscles as an early diagnostic marker for blepharospasm[J]. Rev Neurol, 2012, 55(11): 658-662. |

| [17] | Fayers T, Shaw SR, Hau SC, et al. Changes in corneal aesthesiometry and the sub-basal nerve plexus in benign essential blepharospasm[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2015, 99(11): 1509-1513. DOI: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306426. |

| [18] | Pardal-Fernández JM, Mansilla-Lozano D. Value of simultaneous electromyographic recording of the levator palpebrae and the orbicularis oculi muscles as an early diagnostic marker for blepharospasm[J]. Rev Neurol, 2012, 55(11): 658-662. |

| [19] | Weiss EM, Hershey T, Karimi M, et al. Relative risk of spread of symptoms among the focal onset primary dystonias[J]. Mov Disord, 2006, 21(8): 1175-1181. DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1531-8257. |

| [20] | Clarimon J, Brancati F, Peckham E, et al. Assessing the role of DRD5 and DYT1 in two different case-control series with primary blepharospasm[J]. Mov Disord, 2007, 22(2): 162-166. DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1531-8257. |

| [21] | Xiromerisiou G, Dardiotis E, Tsironi EE, et al. THAP1 mutations in a Greek primary blepharospasm series[J]. Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 2013, 19(4): 404-405. |

| [22] | Defazio G, Abbruzzese G, Aniello MS, et al. Eye symptoms in relatives of patients with primary adult-onset dystonia[J]. Mov Disord, 2012, 27(2): 305-307. DOI: 10.1002/mds.24026. |

| [23] | Balint B, Bhatia KP. Isolated and combined dystonia syndromes-an update on new genes and their phenotypes[J]. Eur J Neurol, 2015, 22(4): 610-617. DOI: 10.1111/ene.2015.22.issue-4. |

| [24] | Copeland NA, Sercombe HE, Ainscough JF, et al. Ciz1 cooperates with cyclin-A-CDK2 to activate mammalian DNA replication in vitro[J]. J Cell Sci, 2010, 12(3): 1108-1115. |

| [25] | Lei L, Wu J, Gu D, et al. CIZ1 interacts with YAP and activates its transcriptional activity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells[J]. Tumour Biol, 2016, 23(6): 21-29. |

| [26] | Dahmcke CM.Buchmann-Moller S, Jensen NA, et al. Altered splicing in exon 8 of the DNA replication factor CIZ1 affects subnuclear distribution and is associated with Alzheimer's disease[J]. Mol Cell Neurosci, 2008, 3(8): 589-594. |

| [27] | Xiao J, Uitti RJ, Zhao Y, et al. Mutations in CIZ1 cause adult onset primary cervical dystonia[J]. Ann Neurol, 2012, 71(4): 458-469. DOI: 10.1002/ana.v71.4. |

| [28] | Liu Q, Niu N, Wada Y, et al. The role of Cdkn1A-interacting Zinc Finger protein 1(CIZ1) in DNA replication and pathophysiology[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2016, 17(2): 121-132. |

| [29] | Higgins G, Roper KM, Watson IJ, et al. Variant Ciz1 is a circulating biomarker for early-stage lung cancer[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 2012, 10(9): E3128-E3135. |

| [30] | Rahman FA, Aziz N, Coverley D. Differential detection of alternatively spliced variants of Ciz1 in normal and cancer cells using a custom exon-junction microarray[J]. BMC Cancer, 2010, 10(3): 482-489. |

| [31] | Wang DQ, Wang K, Yan D, et al. Ciz1 is a novel predictor of survival in human colon cancer[J]. Exp Biol Med, 2014, 23(9): 862-870. |

| [32] | Zhang D, Wang Y, Dai Y, et al. Ciz1 promoted the growth and migration of gallbladder cancer cells[J]. Tumour Biol, 2015, 3(6): 2583-2591. |

| [33] | Liu T, Ren X, Li L, et al. Ciz1 promotes tumorigenicity of prostate carcinoma cells. Front[J]. Biosci, 2015, 20(8): 705-715. |

| [34] | Balint B, Bhatia KP. Dystonia: an update on phenomenology, classification, pathogenesis and treatment[J]. Curr Opin Neurol, 2014, 27(4): 468-476. DOI: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000114. |

| [35] | Loebrich S, Rathje M, Hager E, et al. Genomic mapping and cellular expression of human CPG2 transcripts in the SYNE1 gene[J]. Mol Cell Neurosci, 2016, 71(3): 46-55. |

| [36] | Puckelwartz MJ, Kessler E, Zhang Y, et al. Disruption of nesprin-1 produces an Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy-like phenotype in mice[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2009, 18(4): 607-620. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/ddn386. |

| [37] | Gros-Louis F, Dupré N, Dion P, et al. Mutations in SYNE1 lead to a newly discovered form of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia[J]. Nat Genet, 2007, 39(1): 80-85. DOI: 10.1038/ng1927. |

| [38] | Zhang Q, Bethmann C, Worth NF, et al. Nesprin-1 and-2 are involved in the pathogenesis of Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy and are critical for nuclear envelope integrity[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2007, 16(23): 2816-2833. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/ddm238. |

| [39] | Fanin M, Savarese M, Nascimbeni AC, et al. Dominant muscular dystrophy with a novel SYNE1 gene mutation[J]. Muscle Nerve, 2015, 51(1): 145-147. DOI: 10.1002/mus.v51.1. |

| [40] | Ruegg MA. Organization of synaptic myonuclei by Syne proteins and their role during the formation of the nerve-muscle synapse[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 2005, 102(16): 5643-5644. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0501516102. |

| [41] | Rodriguez-Acevedo AJ, Smith RA, Roy B, et al. Genetic association and gene expression studies suggest that genetic variants in the SYNE1 and TNF genes are related to menstrual migraine[J]. J Headache Pain, 2014, 15(16): 62-65. |

| [42] | Yang W, Zheng H, Wang Y, et al. Nesprin-1 has key roles in the process of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation into cardiomyocyte-like cells in vivo and in vitro[J]. Mol Med Rep, 2015, 11(1): 133-142. |

| [43] | King SJ, Nowak K, Suryavanshi N, et al. Nesprin-1 and nesprin-2 regulate endothelial cell shape and migration[J]. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken), 2014, 71(7): 423-434. DOI: 10.1002/cm.v71.7. |

| [44] | Green EK, Grozeva D, Forty L, et al. Association at SYNE1 in both?bipolar disorder and recurrent major depression[J]. Mol Psychiatry, 2013, 18(5): 614-617. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2012.48. |

| [45] | Nieratschker V, Brückmann C, Plewnia C. CACNA1C risk variant affects facial emotion recognition in healthy individuals[J]. Sci Rep, 2015, 5(1): 17349-17351. |

| [46] | Xu H, Abuhatzira L, Carmona GN, et al. The Ia-2β intronic miRNA, miR-153, is a negative regulator of insulin and dopamine secretion through its effect on the Cacna1c gene in mice[J]. Diabetologia, 2015, 58(10): 2298-2306. DOI: 10.1007/s00125-015-3683-8. |

| [47] | Hamshere ML, Walters JT, Smith R, et al. Genome-wide significant associations in schizophrenia to ITIH3/4, CACNA1C and SDCCAG8, and extensive replication of associations reported by the Schizophrenia PGC[J]. Mol Psychiatry, 2013, 18(6): 708-712. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2012.67. |

| [48] | Heilbronner U, Malzahn D, Strohmaier J, et al. A common risk variant in CACNA1C supports a sex-dependent effect on longitudinal functioning and functional recovery from episodes of schizophrenia-spectrum but not bipolar disorder[J]. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 2015, 25(12): 2262-2270. DOI: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.09.012. |

| [49] | Uemura T, Green M, Warsh JJ. CACNA1C SNP rs1006737 associates with bipolar I disorder independent of the Bcl-2 SNP rs956572 variant and its associated effect on intracellular calcium homeostasis[J]. World J Biol Psychiatry, 2015, 5(1): 1-10. |

| [50] | Langston RG, Rudenko IN, Cookson MR. The function of orthologues of the human Parkinson's disease gene LRRK2 across species: implications for disease modelling in preclinical research[J]. Biochem J, 2016, 473(3): 221-232. DOI: 10.1042/BJ20150985. |

| [51] | Schwab AJ, Ebert AD. Neurite Aggregation and Calcium Dysfunction in iPSC-Derived Sensory Neurons with Parkinson's Disease-Related LRRK2 G2019S Mutation[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2015, 5(6): 1039-1052. DOI: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.11.004. |

| [52] | Bergareche A, Rodríguez-Oroz MC, Estanga A, et al. DAT imaging and clinical biomarkers in relatives at genetic risk for LRRK2 R1441G Parkinson's disease[J]. Mov Disord, 2016, 31(3): 335-343. DOI: 10.1002/mds.26478. |

| [53] | Linnertz C, Lutz MW, Ervin JF, et al. The genetic contributions of SNCA and LRRK2 genes to Lewy Body pathology in Alzheimer's disease[J]. Hum Mol Genet, 2014, 23(18): 4814-4821. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/ddu196. |

| [54] | Akiyama T, Warita H, Kato M, et al. Genotype-phenotype relationships in familial ALS with FUS/TLS mutations in Japan[J]. Muscle Nerve, 2016, 23(18): 414-421. |

| [55] | Masuda A, Takeda JI, Ohno K. FUS-mediated regulation of alternative RNA processing in neurons: insights from global transcriptome analysis[J]. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA, 2016, 23(18): 814-821. |

| [56] | Lourenco GF, Janitz M, Huang Y, et al. Long noncoding RNAs in TDP-43 and FUS/TLS-related frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)[J]. Neurobiol Dis, 2015, 82(1): 445-454. |

| [57] | Weber A, Kreth J, Müller U. Intronic PRRT2 mutation generates novel splice acceptor site and causes paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia with infantile convulsions (PKD/IC) in a three generation family[J]. BMC Med Genet, 2016, 17(1): 16-21. DOI: 10.1186/s12881-016-0281-7. |

| [58] | Paramasivam A, Meena AK, Pedaparthi L, et al. Novel mutation in C10orf2 associated with multiple mtDNA deletions, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia and premature aging[J]. Mitochondrion, 2016, 26: 81-85. DOI: 10.1016/j.mito.2015.12.006. |

| [59] | Dalby AB, Hofr C, Cech TR. Contributions of the TEL-patch amino acid cluster on TPP1 to telomeric DNA synthesis by human telomerase[J]. J Mol Biol, 2015, 427(6 Pt B): 1291-1303. |

| [60] | Dy ME, Sims KB, Friedman J. TPP1 deficiency: Rare cause of isolated childhood-onset progressive ataxia[J]. Neurology, 2015, 85(14): 1259-1261. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001876. |

| [61] | Yu F, Liu XM, Chen YH, et al. A novel CLN2/TPP1 mutation in a patient with late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis[J]. Neurol Sci, 2015, 36(10): 1917-1919. DOI: 10.1007/s10072-015-2272-4. |

| [62] | Murphy TM, Ryan M, Foster T, et al. Risk and protective genetic variants in suicidal behaviour: association with SLC1A2, SLC1A3, 5-HTR1B & NTRK2 polymorphisms[J]. Behav Brain Funct, 2011, 7(1): 22-25. DOI: 10.1186/1744-9081-7-22. |

| [63] | Pons R, Cuenca-León E, Miravet E, et al. Paroxysmal non-kinesigenic dyskinesia due to a PNKD recurrent mutation: report of two Southern European families[J]. Eur J Paediatr Neurol, 2012, 16(1): 86-89. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2011.09.008. |

| [64] | Deng H, Wu Y, Jankovic J. The EIF4G1 gene and Parkinson's disease[J]. Acta Neurol Scand, 2015, 132(2): 73-78. DOI: 10.1111/ane.12397. |

| [65] | Szpisjak L, Obal I, Engelhardt JI, et al. A novel SETX gene mutation producing ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2[J]. Acta Neurol Belg, 2016, 25(2): 73-78. |

| [66] | Elsayed SM, Heller R, Thoenes M, et al. Autosomal dominant SCA5 and autosomal recessive infantile SCA are allelic conditions resulting from SPTBN2mutations[J]. Eur J Hum Genet, 2014, 22(2): 286-288. DOI: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.150. |

| [67] | Jackson PK. TTBK2 kinase: linking primary cilia and cerebellar ataxias[J]. Cell, 2012, 151(4): 697-699. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.027. |

2017, Vol. 38

2017, Vol. 38